Dismantling the Optics of a National Broadband Plan fraught with trouble

The skeletons hidden within the closet are making an appearance, putting Ireland's connectivity dreams on the line.

Published 20/12/18

Optics are beginning to prevail in the most transformative infrastructure project ever devised for Ireland, and beneath the veil of political correctness lies a tainted process hanging by a thread. The dirty secrets of disjointed governments, sloppy regulatory practices and unethical greed held by certain telecoms companies threaten to inflict carnage on our collective vision to end the rural/urban digital divide and stimulate investment in peripheral regions through the provision of world-class connectivity, a fundamental right of every Irish citizen.

The pipe that was once robust is beginning to leak, which will leave behind decimation of unprecedented magnitude, and no person or no company is untouchable in the quest for truth. The surfacing of confounding evidence concerning the National Broadband Plan and other broadband schemes in Ireland is imminent, and the reputation of our state to deliver on its promises has already been thrown into precarity.

The questions which disturb the industry are the ones that will be answered through a series of small but damning revelations which bind together to create a picture worth reflecting upon for future endeavours. Those questions resemble the following lines. How did the National Broadband Plan arrive in the position it is now? How did we allow the development of a one-horse race in which the only remaining horse isn't even fit for purpose? How did we allow a private company to rip up a plan central to economic progress without a fight? How did we allow the impartiality of our telecoms regulator to be compromised?

And, the real kicker, how can we proceed with a process that is jeopardised at its core?

The pipe that was once robust is beginning to leak, which will leave behind decimation of unprecedented magnitude, and no person or no company is untouchable in the quest for truth. The surfacing of confounding evidence concerning the National Broadband Plan and other broadband schemes in Ireland is imminent, and the reputation of our state to deliver on its promises has already been thrown into precarity.

The questions which disturb the industry are the ones that will be answered through a series of small but damning revelations which bind together to create a picture worth reflecting upon for future endeavours. Those questions resemble the following lines. How did the National Broadband Plan arrive in the position it is now? How did we allow the development of a one-horse race in which the only remaining horse isn't even fit for purpose? How did we allow a private company to rip up a plan central to economic progress without a fight? How did we allow the impartiality of our telecoms regulator to be compromised?

And, the real kicker, how can we proceed with a process that is jeopardised at its core?

A Factual Overview

I don't want to bore you by regurgitating the details already covered in relation to the National Broadband Plan, however, a quick summary is necessary to build some context.

The remaining consortium in the process, under the title "National Broadband Ireland", is led by Granahan McCourt and its CEO, David McCourt. Granahan McCourt has sold its stake in eNet, the operator of government-subsidised MANs in Ireland, to the Irish Infrastructure Fund, a semi-state fund controlled by Australian investment managers, AMP Capital, and Irish Life Investment Managers. The National Broadband Ireland consortium is composed of several other companies, including Actavo, Kelly Group, KN Group and Nokia. In light of new information, LukeKehoe.com understands that eNet is no longer a member of the National Broadband Ireland consortium.

David McCourt met with Denis Naughten, former Minister for Communications, and other government ministers privately on a number of occasions during a critical time in the process, and revelations have confirmed that these meetings also occurred during the time that bidders such as eir were still seeking to pursue the plan. An "independent" report conducted by Peter Smyth outlined the opinion that these meetings have not compromised the integrity of the National Broadband Plan but concluded that Denis Naughten's action to resign was a necessary step.

The remaining consortium in the process, under the title "National Broadband Ireland", is led by Granahan McCourt and its CEO, David McCourt. Granahan McCourt has sold its stake in eNet, the operator of government-subsidised MANs in Ireland, to the Irish Infrastructure Fund, a semi-state fund controlled by Australian investment managers, AMP Capital, and Irish Life Investment Managers. The National Broadband Ireland consortium is composed of several other companies, including Actavo, Kelly Group, KN Group and Nokia. In light of new information, LukeKehoe.com understands that eNet is no longer a member of the National Broadband Ireland consortium.

David McCourt met with Denis Naughten, former Minister for Communications, and other government ministers privately on a number of occasions during a critical time in the process, and revelations have confirmed that these meetings also occurred during the time that bidders such as eir were still seeking to pursue the plan. An "independent" report conducted by Peter Smyth outlined the opinion that these meetings have not compromised the integrity of the National Broadband Plan but concluded that Denis Naughten's action to resign was a necessary step.

Open eir is entering the final stages of its FTTH deployment to 300,000 homes which it was afforded the liberty to cherry pick from the original catchment area of the National Broadband Plan. The former state-owned monopoly essentially blackmailed the government into allowing the restructuring of the plan by threatening to raise concerns of state-aid violation under European laws.

This cherry picking has been manipulated in such a way that a leaked government memo determined the cost of connecting the remaining 542,000 homes under the plan will exceed the cost of connecting the original catchment of 842,000 premises. The company has insisted that it will strongly resist any efforts by ComReg or the government to make changes to its regulated access pricing in the inevitable event that National Broadband Ireland must access open eir's wholesale network in rural Ireland.

This cherry picking has been manipulated in such a way that a leaked government memo determined the cost of connecting the remaining 542,000 homes under the plan will exceed the cost of connecting the original catchment of 842,000 premises. The company has insisted that it will strongly resist any efforts by ComReg or the government to make changes to its regulated access pricing in the inevitable event that National Broadband Ireland must access open eir's wholesale network in rural Ireland.

Examining the Credibility of Granahan McCourt

Wading through the information that journalists of other media organisations are forbidden to write about is of paramount importance if we want to understand a picture based on truths, not a politically altered one. As the only remaining bidder in the National Broadband Plan, Granahan McCourt finds itself under intense scrutiny from every angle, and this is a critical process to weed out the lies.

I think one of the most profound subjects which has peaked interests in the National Broadband Plan is the credibility of Granahan McCourt and David McCourt to actually deliver on their ballsy promises. Remember, if we sign off on the current bid, billions of euro of taxpayer's money will be handed over to a company that has never directly designed or deployed a national broadband network in Ireland, or in fact, anywhere on the continent of Europe. Based on that fact alone, approving the current bid would lead us on a crash course to disaster.

Upon the deserting of SSE and John Laing Group, Granahan McCourt incurred irreversible damage, and this is based on a suction of knowledge and expertise in deploying large broadband infrastructure projects. In particular, SSE was viewed as a stalwart company possessing the necessary capacity to deliver the National Broadband Plan. What were their reasons for abandoning David McCourt?

I think one of the most profound subjects which has peaked interests in the National Broadband Plan is the credibility of Granahan McCourt and David McCourt to actually deliver on their ballsy promises. Remember, if we sign off on the current bid, billions of euro of taxpayer's money will be handed over to a company that has never directly designed or deployed a national broadband network in Ireland, or in fact, anywhere on the continent of Europe. Based on that fact alone, approving the current bid would lead us on a crash course to disaster.

Upon the deserting of SSE and John Laing Group, Granahan McCourt incurred irreversible damage, and this is based on a suction of knowledge and expertise in deploying large broadband infrastructure projects. In particular, SSE was viewed as a stalwart company possessing the necessary capacity to deliver the National Broadband Plan. What were their reasons for abandoning David McCourt?

Those closely involved in the tender process of the National Broadband Plan have expressed a stunned reaction to the nature in which Granahan McCourt has interacted with the Department of Communications. It is claimed that many meetings during pivotal stages of the process involved a team of department officials sitting across from one person within the consortium: David McCourt. Need I explain that this is an incredibly peculiar situation to arise for a government infrastructure project of such scale, and other companies have traditionally ensured the presence of representatives from every division during critical talks. The narrative that this is a one-man show is building, and it won't sit well with anyone.

Of course, the investment fund and McCourt himself would point us to their long and, in my view, admirable history of investing in telecoms infrastructure across the world. The issue is, however, Granahan McCourt itself is not a company that handles the rollout of infrastructure internally. ENet was the company that engaged in a pilot FTTH scheme with the government, a requirement which stands as a proof of ability before a consortium can be awarded the National Broadband Plan contract. With eNet now beyond David McCourt's reach, how has the consortium reached this stage in the process without performing its own pilot scheme? This is a basic step that could determine the competence of Granahan McCourt to deploy resilient FTTH connectivity on this island, in a cost and time efficient manner.

Of course, the investment fund and McCourt himself would point us to their long and, in my view, admirable history of investing in telecoms infrastructure across the world. The issue is, however, Granahan McCourt itself is not a company that handles the rollout of infrastructure internally. ENet was the company that engaged in a pilot FTTH scheme with the government, a requirement which stands as a proof of ability before a consortium can be awarded the National Broadband Plan contract. With eNet now beyond David McCourt's reach, how has the consortium reached this stage in the process without performing its own pilot scheme? This is a basic step that could determine the competence of Granahan McCourt to deploy resilient FTTH connectivity on this island, in a cost and time efficient manner.

Ultimately, based on the concrete evidence that we now bestow, it would seem inconceivable that Granahan McCourt could be granted a multi-billion euro contract to connect 542,000 homes in Ireland with high-speed broadband because there is a chronic lack of credibility, derived from holes in the form of existing infrastructure assets and experience in the Irish market. There are a plethora of other sources which produce unsettling conclusions about Granahan McCourt, and if we can't place complete trust in the consortium awarded the National Broadband Plan, the contract should be scrapped.

Eir pulls the Strings

There is a fine line between prioritising investor interests as a private company and defying ethics and basic principles of corporate social responsibility. eir has breached that line to such an extent that its own goals have radically diverged from those of the Irish people. That wasn't always the case, though, as the semi-state monopoly of yesteryear once operated in the wider public interest, before we fatally handed over control of critical infrastructure to private companies.

Many people will loathe, off the record of course, that open eir "gamed the National Broadband Plan beautifully". While such a statement is correct, I don't like to use it because, inadvertently, it conveys the message that eir's moves are worthy of admiration. Obviously, that couldn't be further from the truth.

Many people will loathe, off the record of course, that open eir "gamed the National Broadband Plan beautifully". While such a statement is correct, I don't like to use it because, inadvertently, it conveys the message that eir's moves are worthy of admiration. Obviously, that couldn't be further from the truth.

As explained, the company is in the late stages of its FTTH rollout to 300,000 homes in rural Ireland. For the people covered under this deployment, eir's infrastructure is providing them with access to world-class connectivity in isolated locations which would never have been considered by commercial operators before. And, we need to highlight the fact that this deployment has, indeed, transformed thousands of lives right across Ireland. eir is truly the only fixed operator to provide gigabit-class broadband in rural Ireland, outside towns and their suburbs.

But, as we've come to understand, there is a dark side to this roll-out. It has been widely reported that eir strategically selected the homes to connect in an effort to maximise the number of locations in which the winner of the National Broadband Plan would be forced to access its network. This is deeply concerning, and it introduces the question of how we allowed this situation to materialise in the first place.

Another factor of this rollout which has exacerbated the complexity of the National Broadband Plan is the fact that open eir has deviated from its original plans supplied to the Department of Communications. To clarify, some of the homes that were earmarked for connection under the plan which eir submitted initially will not have access to its network. The company is changing the homes that will make up the 300,000 threshold on a constant basis, and this forces planners of the National Broadband Plan to redraw their intervention area map upon notification from eir. The laws and the regulator are on eir's side, and any form of state intervention cannot involve overlap with their wholesale network.

But, as we've come to understand, there is a dark side to this roll-out. It has been widely reported that eir strategically selected the homes to connect in an effort to maximise the number of locations in which the winner of the National Broadband Plan would be forced to access its network. This is deeply concerning, and it introduces the question of how we allowed this situation to materialise in the first place.

Another factor of this rollout which has exacerbated the complexity of the National Broadband Plan is the fact that open eir has deviated from its original plans supplied to the Department of Communications. To clarify, some of the homes that were earmarked for connection under the plan which eir submitted initially will not have access to its network. The company is changing the homes that will make up the 300,000 threshold on a constant basis, and this forces planners of the National Broadband Plan to redraw their intervention area map upon notification from eir. The laws and the regulator are on eir's side, and any form of state intervention cannot involve overlap with their wholesale network.

When a memo states that connecting 542,000 homes under the National Broadband Plan will be more expensive than connecting the original 842,000 homes, we should understand that something has gone seriously wrong. The charges associated with accessing open eir's network are regulated by ComReg, and the company argues that setting a special rate for the National Broadband Plan would undermine competition in the broadband market and lessen its ability to maintain expensive duct and pole infrastructure in rural Ireland. It is noteworthy, however, that deploying resilient broadband networks on this island is amongst the most expensive in Europe thanks to our topography and distributed population, so we should expect to pay more for a similar service provided in a neighbouring country. I think this point is often ignored by third-party retailers.

The above isn't the only concern raised about the cost of accessing open eir's infrastructure in Ireland. Sky recently lodged an appeal to the High Court against the changes included in ComReg's Broadband Market Review, which will allow open eir to charge retailers €170 for connection or migration on their network. This move by ComReg will solidify open eir's monopoly in rural Ireland and deter consumers from switching between networks if retailers don't swallow the charges. In this way, open eir will benefit financially from a high rate of churn on its FTTH network, an absurd pricing system that could see the 300,000 homes targeted under open eir's infrastructure overpay for the network by €75 million over the next five years.

The above isn't the only concern raised about the cost of accessing open eir's infrastructure in Ireland. Sky recently lodged an appeal to the High Court against the changes included in ComReg's Broadband Market Review, which will allow open eir to charge retailers €170 for connection or migration on their network. This move by ComReg will solidify open eir's monopoly in rural Ireland and deter consumers from switching between networks if retailers don't swallow the charges. In this way, open eir will benefit financially from a high rate of churn on its FTTH network, an absurd pricing system that could see the 300,000 homes targeted under open eir's infrastructure overpay for the network by €75 million over the next five years.

Questioning ComReg's Impartiality

Pointing all of the blame towards eir is not justified, after all, it is ComReg that has allowed the company's wholesale arm to bask in the glory of unchallenged market dominance for a period spanning decades. There is a widespread and credible belief that the regulator's practices favour eir over other telecoms companies, and if this is the case, it could have massive ramifications for the Irish market.

The fundamental role of a regulator or watchdog is to ensure a healthy market is available for consumers, and that companies abide by the rules. Without robust regulatory oversight, companies can do what they want, when they want, creating a toxic environment for consumers. Drift your eyes to the invasive tactics used by Facebook to exploit customer data as a real-life example of why we need laws to protect consumers.

Back to the former, a large proportion of the people which hold high positions of power within ComReg are past members of eir. Take what you will from that. Of course, they may be the most experienced individuals for the role in question, but experience is futile if it is corrupted by bias.

Frankly, I can tell you that large swathes of the industry outside of eir are incredibly pissed off with ComReg, and that frustration is having a snowball effect. You see, some of the moves made by ComReg to strengthen eir's monopoly are so flawed and so debilitating for competition in the Irish market that one could only ask where the strings were pulled. It is telling that something is seriously wrong when an entire lobbying group of broadband retailers, ALTO, had to be established to call for reforms in the market. ComReg should be the driver of reform, not an external lobbying group.

The fundamental role of a regulator or watchdog is to ensure a healthy market is available for consumers, and that companies abide by the rules. Without robust regulatory oversight, companies can do what they want, when they want, creating a toxic environment for consumers. Drift your eyes to the invasive tactics used by Facebook to exploit customer data as a real-life example of why we need laws to protect consumers.

Back to the former, a large proportion of the people which hold high positions of power within ComReg are past members of eir. Take what you will from that. Of course, they may be the most experienced individuals for the role in question, but experience is futile if it is corrupted by bias.

Frankly, I can tell you that large swathes of the industry outside of eir are incredibly pissed off with ComReg, and that frustration is having a snowball effect. You see, some of the moves made by ComReg to strengthen eir's monopoly are so flawed and so debilitating for competition in the Irish market that one could only ask where the strings were pulled. It is telling that something is seriously wrong when an entire lobbying group of broadband retailers, ALTO, had to be established to call for reforms in the market. ComReg should be the driver of reform, not an external lobbying group.

As an example, ComReg slapped open eir with a €3 million fine for breaching its role as a wholesale provider, which included giving priority access to its retail division over those of external retailers such as Vodafone. However, if we dig beneath this fine, it becomes immediately obvious that eir has banked millions, in the hundreds, from its wholesale practices. The company is laughing, at the expense of the integrity of the wider telecoms industry on this island.

The establishment of another regulator to oversee separate aspects of our telecoms infrastructure, such as dark fibre networks, has been suggested and it is something that the Department of Communications is pondering. This would be a mistake, creating unnecessary complexity and further uncertainty in a market that is rife with qualm. Founding a separate regulatory body to ComReg is not the answer, focusing on fixing the one that we already have is.

The regulatory system that we have relied upon for years has failed, and miserably too. Now, more than ever, we need an impartial regulator which wields the power to punish those that defy the rules in place to protect consumers and a regulator which promotes investment in infrastructure through reducing complexities and maintaining a competitive market.

The establishment of another regulator to oversee separate aspects of our telecoms infrastructure, such as dark fibre networks, has been suggested and it is something that the Department of Communications is pondering. This would be a mistake, creating unnecessary complexity and further uncertainty in a market that is rife with qualm. Founding a separate regulatory body to ComReg is not the answer, focusing on fixing the one that we already have is.

The regulatory system that we have relied upon for years has failed, and miserably too. Now, more than ever, we need an impartial regulator which wields the power to punish those that defy the rules in place to protect consumers and a regulator which promotes investment in infrastructure through reducing complexities and maintaining a competitive market.

Ireland's Telecoms Industry has a transparency problem

This meander in the article will raise the eyebrows of many, and that's a testament to the far-reaching breadth of the transparency issue.

In proverbial terms, the mass refusal of people within the telecoms industry to openly share their thoughts about the National Broadband Plan takes the biscuit for the most frustrating aspect of this situation. We are not members of a totalitarian regime, and while industry heads may have been told exactly what to say, word by word, it paints a dystopian image of closed doors and a chronic lack of transparency across the entire spectrum of telecoms companies in Ireland.

In some cases, the group of people that would benefit most from a successful National Broadband Plan are the ones that don't speak up. Is there a reason why the Irish Farmers Association (IFA) has maintained its silence on the issue of high-speed broadband in rural Ireland following a decision to back open eir's bid for the plan. Of course, that decision was swayed by nothing other than the money that these organisations receive from private telecoms companies. Farmers that require connectivity to operate in a modern agricultural environment don't care who provides them with broadband, it just needs to work.

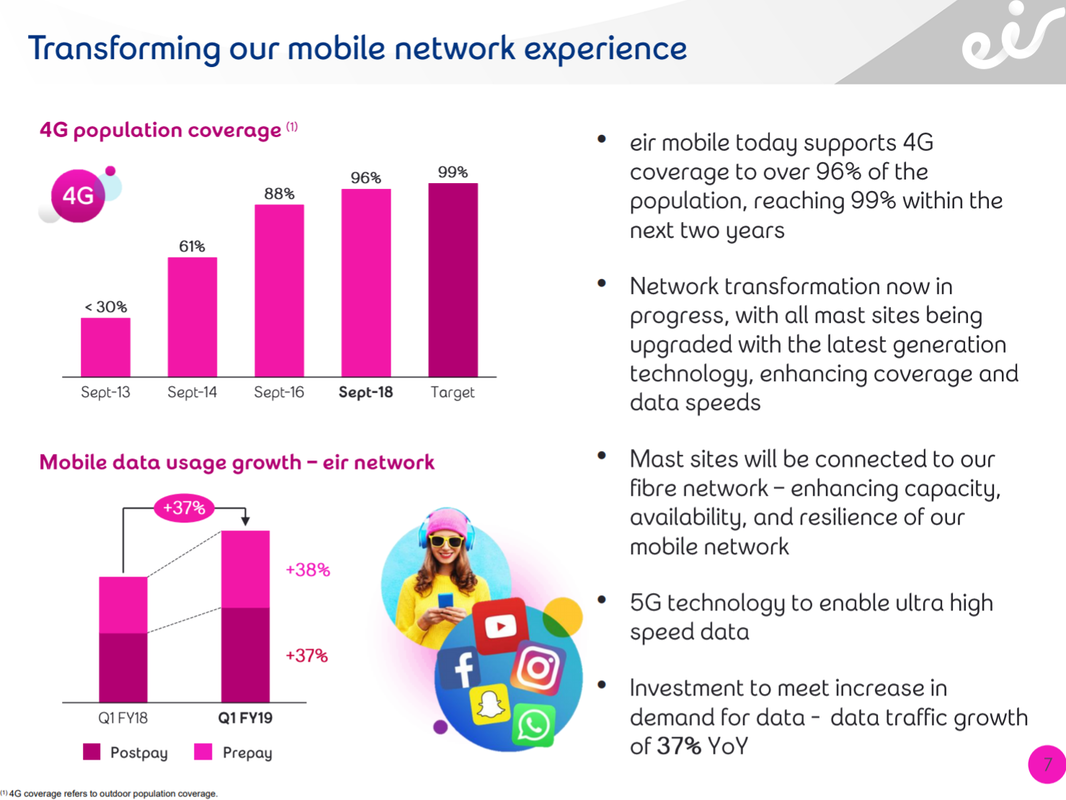

How did eir get away with blatantly lying to its customers and to the media, claiming that the company would embark on a network expansion of unprecedented scale to provide 99% 4G geographic coverage on the island of Ireland? This was explained during interviews, both in the mediums of written articles and radio. Hidden within a presentation referencing coverage achievements lay a detail which eir didn't tell us: the 99% coverage goal refers to population coverage. In particular, I view this event as an epiphany to portray the new low that we've landed ourselves in, a low which erodes the sense of trust that the telecoms industry has fought to regain.

In proverbial terms, the mass refusal of people within the telecoms industry to openly share their thoughts about the National Broadband Plan takes the biscuit for the most frustrating aspect of this situation. We are not members of a totalitarian regime, and while industry heads may have been told exactly what to say, word by word, it paints a dystopian image of closed doors and a chronic lack of transparency across the entire spectrum of telecoms companies in Ireland.

In some cases, the group of people that would benefit most from a successful National Broadband Plan are the ones that don't speak up. Is there a reason why the Irish Farmers Association (IFA) has maintained its silence on the issue of high-speed broadband in rural Ireland following a decision to back open eir's bid for the plan. Of course, that decision was swayed by nothing other than the money that these organisations receive from private telecoms companies. Farmers that require connectivity to operate in a modern agricultural environment don't care who provides them with broadband, it just needs to work.

How did eir get away with blatantly lying to its customers and to the media, claiming that the company would embark on a network expansion of unprecedented scale to provide 99% 4G geographic coverage on the island of Ireland? This was explained during interviews, both in the mediums of written articles and radio. Hidden within a presentation referencing coverage achievements lay a detail which eir didn't tell us: the 99% coverage goal refers to population coverage. In particular, I view this event as an epiphany to portray the new low that we've landed ourselves in, a low which erodes the sense of trust that the telecoms industry has fought to regain.

We need to solve this, not sometime afar into the future, but today. Those who have read article upon article, scanned through transcripts of hearings, and delved into bottomless progress reports will understand that the quality of reporting around this subject has been incredibly poor. Plucking costing figures out of thin air, constantly pushing for the use of wireless technologies, and raising ludicrous alarms of low-take up stand out as low points in the coverage of the National Broadband Plan. In many cases, reporters have neglected to write articles in the fear of being slapped silly with defamation lawsuits. Simply exposing the truth can end a journalist's career, understand the problem?

However, this issue isn't just one that plagues the media, it's one that lurks in the dark side of the Irish telecoms industry. How bad is it when enquiries about coverage are shunned, when employees are told to keep their mouths shut, and when simple questions around pricing structures are ignored, all in the name of "commercial sensitivity".

The secrecy stigma can be tackled, and promoting open discussion between government agencies, telecoms companies and the wider public are stepping stones to a brighter future. The Mobile Phone and Broadband Taskforce has acted as a platform for combating our connectivity woes through industry collaboration, and its mission to annihilate blackspots in Ireland should be a goal shared by every Irish business and citizen. The task force has achieved some tremendous work in its short life thus far, work such as the mandatory implementation of ducting along Ireland's National primary/secondary road network. This is progress which could not be achieved without consultation.

In the end, the level of transparency that the telecoms industry wishes to pursue is determined by none other than itself, and as a member, I wholeheartedly believe that knocking down barriers is the only path to an equilibrium which is in the interests of the people.

However, this issue isn't just one that plagues the media, it's one that lurks in the dark side of the Irish telecoms industry. How bad is it when enquiries about coverage are shunned, when employees are told to keep their mouths shut, and when simple questions around pricing structures are ignored, all in the name of "commercial sensitivity".

The secrecy stigma can be tackled, and promoting open discussion between government agencies, telecoms companies and the wider public are stepping stones to a brighter future. The Mobile Phone and Broadband Taskforce has acted as a platform for combating our connectivity woes through industry collaboration, and its mission to annihilate blackspots in Ireland should be a goal shared by every Irish business and citizen. The task force has achieved some tremendous work in its short life thus far, work such as the mandatory implementation of ducting along Ireland's National primary/secondary road network. This is progress which could not be achieved without consultation.

In the end, the level of transparency that the telecoms industry wishes to pursue is determined by none other than itself, and as a member, I wholeheartedly believe that knocking down barriers is the only path to an equilibrium which is in the interests of the people.

Ripe for a Reformation

I understand that some of the suggestions brought under scrutiny in this article will shock and offend a particular group of people, but they shouldn't because every company and individual referenced has played a respectable role in the quest to ending the rural/urban digital divide, and we cannot ignore their meaningful contributions. This is a collective effort which is bound by a simple equation: a strive for government, telecoms companies and ordinary citizens to work together in an effort to achieve something that is in the interests of an entire nation.

A resistance to transparency, at corporate and government level, renders this equation obsolete. The purpose of this article is to dismantle the optics of the National Broadband Plan, and upon conclusion, the belief that state intervention is required to provide pervasive high-speed broadband connectivity in Ireland is supported by simple facts of economics.

We just need to ask ourselves if we are comfortable to hand over our trust to the consortium fighting to win the National Broadband Plan contract, front-lined by Granahan McCourt and David McCourt. Purely based on the conclusions that I have reviewed, a lack of experience and existing infrastructure assets in the Irish market, combined with evidence of a cosy relationship between certain members of the consortium and the Irish government, and concerns of a price tag that has inflated in the absence of competing bidders causes a National Broadband Ireland bid to become an unpalatable one.

Remember, this is the largest infrastructure project of its kind, not just on this island, but across the continent of Europe. The idea that we should sign the contract because there is only one company left willing to pursue the process is flawed to an extreme.

Allowing eir to cherry pick homes to its heart's desire, without attaching some condition was nonsensical, and it is one of the largest contributors to the bleak situation that we have found ourselves in. There are substantial lessons to learn from this, and it is painfully obvious that enhanced regulatory oversight is now a must, and such oversight must be impartial.

A resistance to transparency, at corporate and government level, renders this equation obsolete. The purpose of this article is to dismantle the optics of the National Broadband Plan, and upon conclusion, the belief that state intervention is required to provide pervasive high-speed broadband connectivity in Ireland is supported by simple facts of economics.

We just need to ask ourselves if we are comfortable to hand over our trust to the consortium fighting to win the National Broadband Plan contract, front-lined by Granahan McCourt and David McCourt. Purely based on the conclusions that I have reviewed, a lack of experience and existing infrastructure assets in the Irish market, combined with evidence of a cosy relationship between certain members of the consortium and the Irish government, and concerns of a price tag that has inflated in the absence of competing bidders causes a National Broadband Ireland bid to become an unpalatable one.

Remember, this is the largest infrastructure project of its kind, not just on this island, but across the continent of Europe. The idea that we should sign the contract because there is only one company left willing to pursue the process is flawed to an extreme.

Allowing eir to cherry pick homes to its heart's desire, without attaching some condition was nonsensical, and it is one of the largest contributors to the bleak situation that we have found ourselves in. There are substantial lessons to learn from this, and it is painfully obvious that enhanced regulatory oversight is now a must, and such oversight must be impartial.

In 2019, let's make it a year of reformation for the telecoms industry in Ireland. We will take an axe to the boundaries of secrecy, place value on a company's industry experience before we appoint government contracts and work to provide the regulator with adequate and impartial staffing while also increasing its powers to ensure a fairer market is accessible by Irish consumers.

But, above all, we will come together with a shared vision to invest in our future through investing in telecoms infrastructure, the electricity of the twenty-first century, and the means by which Ireland can enable its population to thrive at home, at work and in schools across the island. A Gigabit Society is a society in which there is a uniform balance between connectivity availability, for the rich and for the destitute, and for those that live beneath the soaring hills or criss-cross our buzzing cities.

But, above all, we will come together with a shared vision to invest in our future through investing in telecoms infrastructure, the electricity of the twenty-first century, and the means by which Ireland can enable its population to thrive at home, at work and in schools across the island. A Gigabit Society is a society in which there is a uniform balance between connectivity availability, for the rich and for the destitute, and for those that live beneath the soaring hills or criss-cross our buzzing cities.