Messing with the National Broadband Plan is a perilous precedent for Ireland.

Kicking the connectivity can down the road is an effective middle finger to rural Ireland.

Published 26/04/2019

Updated 29/04/2019

This article was updated, upon request of enet, to clarify that enet is not a member of the National Broadband Ireland consortium. Rather, it is envisaged that enet would be a supplier in the future, if the National Broadband Plan contract is successfully awarded to National Broadband Ireland.

Further to the above request, a correction has been made to clarify that both enet and ETNL are wholesale companies - one being the Managed Service Entity for the MANs (enet) and the other (ETNL) commercialising its own assets (backhaul, proprietary metro networks, etc).

This article was updated, upon request of enet, to clarify that enet is not a member of the National Broadband Ireland consortium. Rather, it is envisaged that enet would be a supplier in the future, if the National Broadband Plan contract is successfully awarded to National Broadband Ireland.

Further to the above request, a correction has been made to clarify that both enet and ETNL are wholesale companies - one being the Managed Service Entity for the MANs (enet) and the other (ETNL) commercialising its own assets (backhaul, proprietary metro networks, etc).

I see a country disconnected. Not how it should be, but how it is. A product of successive cataclysmic failures, dipping into minefield areas of flawed regulatory oversight, insufficient state intervention and a market at the mercy of a privatised incumbent operator whose philosophy of under-investment beams brighter than ever.

I see a government that wants to connect the disconnected. 990,000-strong, the disconnected implore for those in the establishment to listen to their woes, intensifying every day as even basic state-services now require high-speed broadband. But this is a government fraught with a confliction of interests, staggering haphazardly between priorities of optics and fibre optics.

I see a bruised National Broadband Plan. Limping in far from idyllic conditions, it formidably sustains blow after blow. The sole remaining consortium, now fundamentally different from the one that entered the process, faces serious questions. National Broadband Ireland's credibility is on thin ice.

I see storms brewing in the face of cost and ownership. As one of the most ambitious infrastructure projects ever undertaken by our country, akin to electrification, the bill will be spread across decades, and ultimately provide massive sums in return to Ireland's economy. Fibre will be its lifeblood, meeting the 150Mbps criteria, and acting as a future-proof transport network that can be leveraged to aid the deployment of sub-6GHz and mmWave 5G NR.

I see a government that wants to connect the disconnected. 990,000-strong, the disconnected implore for those in the establishment to listen to their woes, intensifying every day as even basic state-services now require high-speed broadband. But this is a government fraught with a confliction of interests, staggering haphazardly between priorities of optics and fibre optics.

I see a bruised National Broadband Plan. Limping in far from idyllic conditions, it formidably sustains blow after blow. The sole remaining consortium, now fundamentally different from the one that entered the process, faces serious questions. National Broadband Ireland's credibility is on thin ice.

I see storms brewing in the face of cost and ownership. As one of the most ambitious infrastructure projects ever undertaken by our country, akin to electrification, the bill will be spread across decades, and ultimately provide massive sums in return to Ireland's economy. Fibre will be its lifeblood, meeting the 150Mbps criteria, and acting as a future-proof transport network that can be leveraged to aid the deployment of sub-6GHz and mmWave 5G NR.

The Lowdown on the Slowdown

Retelling the story of the past in a way that alters fundamental details has become second-nature for the current government. In a desperate search for excuses to explain why the National Broadband Plan has not been delivered, and why its price-tag continues to climb, the government has put the spin machine on full power.

The categorisation of high-speed broadband has moved from 30Mbps to 150Mbps, a striking reminder of just how much our connectivity needs have evolved in the past seven years.

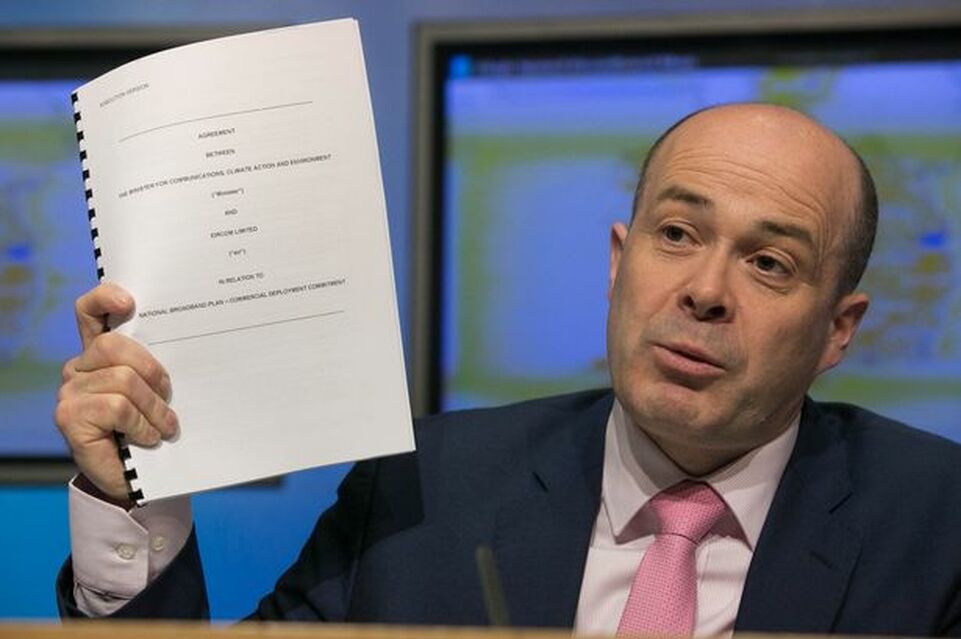

Recently, it claimed that the current National Broadband Plan is radically different from the one first announced by Pat Rabbitte, then Minister for Communications, in 2012. To some extent, this is true. Importantly, the categorisation of high-speed broadband has moved from 30Mbps to 150Mbps, a striking reminder of just how much our connectivity needs have evolved in the past seven years.

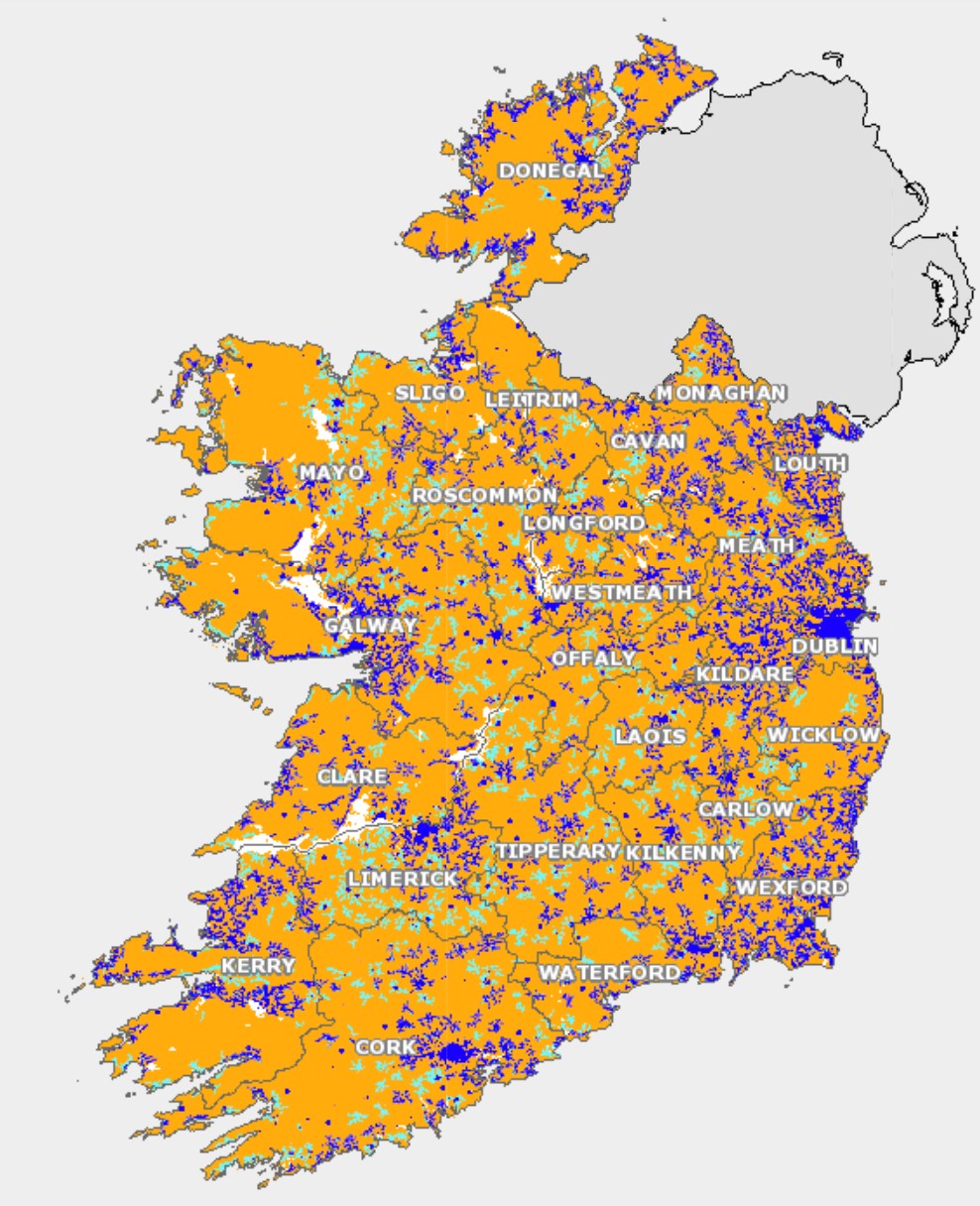

The scope of state intervention has changed too, on a seismic scale. In 2012, the government intended to "develop an intervention to deliver minimum speeds of between 30 and 40Mbps to the other 50% of the population which would not be achieved on a commercial basis". Today, the National Broadband Plan will include 21% of Ireland's population, representing 22.8% (543,000) of premises on this island.

This shrinking in size of the state intervention amber area has been driven by an increase in high-speed broadband availability amongst commercial operators. Since the plan was initially conceptualised, urban and suburban areas have been connected to open eir's FTTC network (up to 100Mbps), Virgin Media's DOCSIS 3 network (up to 500Mbps) and SIRO's FTTH network (up to 1,000Mbps).

The scope of state intervention has changed too, on a seismic scale. In 2012, the government intended to "develop an intervention to deliver minimum speeds of between 30 and 40Mbps to the other 50% of the population which would not be achieved on a commercial basis". Today, the National Broadband Plan will include 21% of Ireland's population, representing 22.8% (543,000) of premises on this island.

This shrinking in size of the state intervention amber area has been driven by an increase in high-speed broadband availability amongst commercial operators. Since the plan was initially conceptualised, urban and suburban areas have been connected to open eir's FTTC network (up to 100Mbps), Virgin Media's DOCSIS 3 network (up to 500Mbps) and SIRO's FTTH network (up to 1,000Mbps).

It is of paramount importance to remember that the state cannot provide subsidised services in areas where commercial operators are present. This has been highlighted by open eir's rural FTTH build-out, which will pass 335,000 cherry-picked premises that were covered under the National Broadband Plan upon completion in June of this year. Adding to the complexity, open eir will also provide FTTH services to 50,000 urban in-fill premises that currently fall in the amber area for state intervention.

These minimum speed and intervention area changes to the National Broadband Plan are in response to an evolution of market conditions over a course of seven years and are required to maintain its integrity. The dramatic change in the number of rural premises that can be considered commercially viable for private operators to pass with high-speed broadband is a result of diving CapEx and OpEx requirements with fibre infrastructure.

Despite the above changes, the fundamental purpose of the National Broadband Plan has persisted. But moving back to one of the opening details, the current government has tried to articulate a message that the fundamentals of the National Broadband Plan have changed. This is a blatant lie to the Irish people.

These minimum speed and intervention area changes to the National Broadband Plan are in response to an evolution of market conditions over a course of seven years and are required to maintain its integrity. The dramatic change in the number of rural premises that can be considered commercially viable for private operators to pass with high-speed broadband is a result of diving CapEx and OpEx requirements with fibre infrastructure.

Despite the above changes, the fundamental purpose of the National Broadband Plan has persisted. But moving back to one of the opening details, the current government has tried to articulate a message that the fundamentals of the National Broadband Plan have changed. This is a blatant lie to the Irish people.

Examining these "changes" in greater detail, it is now claimed that the original purpose of the National Broadband Plan was to build a fibre backhaul network to thousands of villages and towns in Ireland, with the view that commercial operators such as open eir would leverage this transport network to connect premises with a last-mile access network.

Of course, if this was the initial objective of the National Broadband Plan, it would differ vastly from what we have today. Unfortunately, however, the government has spewed out this information without actually providing any evidence to support it. On the contrary, there are droves of documents, many of which can be found on government-run sites, to support the view that the National Broadband Plan was always intended to be both an access and transport network.

Of course, if this was the initial objective of the National Broadband Plan, it would differ vastly from what we have today. Unfortunately, however, the government has spewed out this information without actually providing any evidence to support it. On the contrary, there are droves of documents, many of which can be found on government-run sites, to support the view that the National Broadband Plan was always intended to be both an access and transport network.

By spinning a story that today's National Broadband Plan is radically different from yesterday's, the government can open a loophole for itself to jump through, placating those who have questioned the uplift in costs.

And, obviously, the government's pivot in narrative has a reasoning behind it: cost escalation. The Irish people are genuinely worried about the volume of state-subsidisation that the National Broadband Plan will require. Many figures have been floating around, strangely all without any publication of cost analysis, and most are multiples of that projected in 2012.

By spinning a story that today's National Broadband Plan is radically different from yesterday's, the government can open a loophole for itself to jump through, placating those who have questioned the uplift in costs. Separately, some suggest that these high figures, in the region of €3 billion, have been touted by senior members of the government in a strategic effort to turn public opinion against the plan, leading to its cancellation.

By spinning a story that today's National Broadband Plan is radically different from yesterday's, the government can open a loophole for itself to jump through, placating those who have questioned the uplift in costs. Separately, some suggest that these high figures, in the region of €3 billion, have been touted by senior members of the government in a strategic effort to turn public opinion against the plan, leading to its cancellation.

If we dig deeper into the cost aspect, it becomes immediately apparent that the proverbial term, not to judge a book by its cover, is relevant. The National Broadband Plan is a multi-decade infrastructure project whose cost cannot be gauged in a vacuum of constantly changing external market conditions and advances in broadband delivery technology. The criticality of understanding this cannot be underestimated.

When people hear figures such as the aforementioned €3 billion quoted in the media, understandably, it unsettles their stomach. But, this cost will be spread across twenty-five years, equalling little more than €120 million in state subsidisation annually. And, if we contrast the cost of the ambitious project to the enormous value it will create for the Irish economy, it is clear that this is a good deal for Ireland.

Touching on that last point, the contribution of broadband to Ireland's economic and social development is often overlooked. Think of how electrification paved the way for entirely new industries dependent on it, and how universal access to electricity has markedly improved the quality of life in Ireland. Now apply that to high-speed broadband, today and tomorrow's equivalent of electrification.

Frankly, the realm of benefits which high-speed broadband will create for Ireland is so far-reaching, so profound that no one can provide a comprehensive overview of. Some key beneficiaries include remote working, a precedent which can mitigate issues associated with urbanisation in cities such as Dublin and reduce the growing income divide between rural and urban regions.

When people hear figures such as the aforementioned €3 billion quoted in the media, understandably, it unsettles their stomach. But, this cost will be spread across twenty-five years, equalling little more than €120 million in state subsidisation annually. And, if we contrast the cost of the ambitious project to the enormous value it will create for the Irish economy, it is clear that this is a good deal for Ireland.

Touching on that last point, the contribution of broadband to Ireland's economic and social development is often overlooked. Think of how electrification paved the way for entirely new industries dependent on it, and how universal access to electricity has markedly improved the quality of life in Ireland. Now apply that to high-speed broadband, today and tomorrow's equivalent of electrification.

Frankly, the realm of benefits which high-speed broadband will create for Ireland is so far-reaching, so profound that no one can provide a comprehensive overview of. Some key beneficiaries include remote working, a precedent which can mitigate issues associated with urbanisation in cities such as Dublin and reduce the growing income divide between rural and urban regions.

Cost aside, the National Broadband Plan has also had to weather other storms, primary of which being ownership. After all, it is the Irish people that will be asked to fork out for this infrastructure, and once roll-out commences, a reversal would be almost inconceivable. The question of ownership comes down to whether it is in the interest of Ireland to hand over control of critical infrastructure, funded by taxpayers, to a private entity.

Moreover, the wholesale open access model exhibited by the network will need to be patrolled and regulated with incredible intricacy to ensure fair treatment of retailers, something that some of Ireland's established telecoms operators have defied in the past. This means devoting resources and meaningful regulatory power to an impartial body similar in function to ComReg or the Department of Communications.

Moreover, the wholesale open access model exhibited by the network will need to be patrolled and regulated with incredible intricacy to ensure fair treatment of retailers, something that some of Ireland's established telecoms operators have defied in the past. This means devoting resources and meaningful regulatory power to an impartial body similar in function to ComReg or the Department of Communications.

The question of ownership comes down to whether it is in the interest of Ireland to hand over control of critical infrastructure, funded by taxpayers, to a private entity.

In a world free from imperfections, Ireland's people should own and control their national broadband network, just as they do with electricity and water today. Public ownership of vital utilities gives us tremendous power to affect change where it is required, and to ensure that universal provision is met without hindrance.

Guaranteeing these same foundational principles becomes exponentially more difficult when shareholders are involved in the operation of national infrastructure. The only line of defence with private ownership is the regulator, whose powers are intrinsically limited.

Guaranteeing these same foundational principles becomes exponentially more difficult when shareholders are involved in the operation of national infrastructure. The only line of defence with private ownership is the regulator, whose powers are intrinsically limited.

Personally, I am of the belief that public ownership of the National Broadband Plan, if it were viable, would be the best outcome for Ireland and the only one that could categorically guarantee equal access to broadband services across our island.

However, the current vision of the National Broadband Plan is based on private ownership and operation after a period of over twenty-five years. This ownership model has its benefits and, importantly, it excels where a public model falls down. In fact, external firms contracted on behalf of the government, which specialise in market analysis, recommend private ownership of the National Broadband Plan.

These recommendations, put forward by firms such as KPMG, broadcast the view that private ownership of the wholesale network, combined with contractual obligations, provides an incentive to invest in the network as a measure of future-proofing and to exploit more revenue streams. Additionally, the cost burden to the state is likely to be lower with private ownership, both in terms of upfront capital and long-term operational expenses.

A greater abundance of skill for the design, construction and operation of the National Broadband Plan exists in the private sector, something unique to private ownership. This private model also reduces the risk to the public sector, with most of it being borne by the private entity.

However, the current vision of the National Broadband Plan is based on private ownership and operation after a period of over twenty-five years. This ownership model has its benefits and, importantly, it excels where a public model falls down. In fact, external firms contracted on behalf of the government, which specialise in market analysis, recommend private ownership of the National Broadband Plan.

These recommendations, put forward by firms such as KPMG, broadcast the view that private ownership of the wholesale network, combined with contractual obligations, provides an incentive to invest in the network as a measure of future-proofing and to exploit more revenue streams. Additionally, the cost burden to the state is likely to be lower with private ownership, both in terms of upfront capital and long-term operational expenses.

A greater abundance of skill for the design, construction and operation of the National Broadband Plan exists in the private sector, something unique to private ownership. This private model also reduces the risk to the public sector, with most of it being borne by the private entity.

However, while many of these arguments for private ownership of the National Broadband Plan are valid, some of the other ones that were initially put forward are not. A prime example of this is the view that a tender-based approach on private ownership would invigorate greater competition for the National Broadband Plan contract, and consequently drive prices down.

Of course, today's ridiculous situation, with only one renaming consortium intending to deliver the largest infrastructure project Ireland has ever seen, would debunk the above viewpoint. This is a one-horse-race which isn't even deserving of the title "race". It is ludicrous to suggest that the absence of competition will not adversely impact the National Broadband Plan in areas of cost and deployment strategy.

Of course, today's ridiculous situation, with only one renaming consortium intending to deliver the largest infrastructure project Ireland has ever seen, would debunk the above viewpoint. This is a one-horse-race which isn't even deserving of the title "race". It is ludicrous to suggest that the absence of competition will not adversely impact the National Broadband Plan in areas of cost and deployment strategy.

The above is a perfect segue away from ownership and towards the remaining consortium. For clarity, National Broadband Ireland, composed of Actavo, Kelly Group, KN Group and Nokia, is led by Granahan McCourt Capital (GMC). Oddly, many details surrounding this New York-based private investment firm remain nebulous, and this fills me with a sense of foreboding for troubles to come.

What we do know is that Granahan McCourt Capital specialises in investing in small and medium-sized companies, most of which lie in the fields of government, media, technology and telecommunications. Further to this, it seeks to invest in companies for a period of between two and four years. As you could guess, the scale of the National Broadband Plan would be a confounding outlier in its portfolio of investments.

This brings us to a fundamental question. Can Granahan McCourt Capital actually fulfil an infrastructure project of such scale?

What we do know is that Granahan McCourt Capital specialises in investing in small and medium-sized companies, most of which lie in the fields of government, media, technology and telecommunications. Further to this, it seeks to invest in companies for a period of between two and four years. As you could guess, the scale of the National Broadband Plan would be a confounding outlier in its portfolio of investments.

This brings us to a fundamental question. Can Granahan McCourt Capital actually fulfil an infrastructure project of such scale?

Oddly, many details surrounding this New York-based private investment firm remain nebulous, and this fills me with a sense of foreboding for troubles to come.

It is also key to understand the role of enet, which will be a supplier to the consortium. This is where the web of complexities stretches beyond what one could imagine. Up until late last year, Granahan McCourt Capital held a stake in enet.

It then emerged that Granahan McCourt Capital had sold its remaining stake in enet to the Irish Infrastructure Fund (IFF), a state-backed fund managed by Australian investment managers AMP Capital and Irish Life Investment Managers.

Enet is a managed service entity overseeing the operation of ninety-four Metropolitan Area Networks (MANs) on behalf of the state. Within enet, there are two wholesale divisions enet enet Telecommunications Networks Limited or ETNL.

Enet offers co-location, managed services, dark fibre, sub-ducts and ducts using the MANs infrastructure. The company also manages connections to the MANs by external retailers such as SIRO. Its sales team is responsible for selling these services, and also those of ETNL. Internal transfer pricing is determined by ETNL, and its NOC oversees the infrastructure of both companies, which includes enet's MANs and ETNL's national fixed/wireless backhaul.

Being members of the same parent company, there was a potential for a conflict of interest between enet and ETNL and an incentive to favour customers who access products and services using the company's combined infrastructure. Over time, the development of ETNL alongside enet moved its categorisation from a managed service entity to an operator.

Enet is a managed service entity overseeing the operation of ninety-four Metropolitan Area Networks (MANs) on behalf of the state. Within enet, there are two wholesale divisions enet enet Telecommunications Networks Limited or ETNL.

Enet offers co-location, managed services, dark fibre, sub-ducts and ducts using the MANs infrastructure. The company also manages connections to the MANs by external retailers such as SIRO. Its sales team is responsible for selling these services, and also those of ETNL. Internal transfer pricing is determined by ETNL, and its NOC oversees the infrastructure of both companies, which includes enet's MANs and ETNL's national fixed/wireless backhaul.

Being members of the same parent company, there was a potential for a conflict of interest between enet and ETNL and an incentive to favour customers who access products and services using the company's combined infrastructure. Over time, the development of ETNL alongside enet moved its categorisation from a managed service entity to an operator.

On top of these concerns lies another. Enet's two state contracts were renewed in 2017, two years before its first one was scheduled to expire. There was no tender process, meaning rivals such as BT who expressed interest to compete against enet in a competitive nature were told that it was too late. How was this allowed to happen?

It is clear that regulatory oversight, managed by the Department of Communications in the case of enet, has failed. History is destined to repeat itself with the National Broadband Plan.

It is clear that regulatory oversight, managed by the Department of Communications in the case of enet, has failed. History is destined to repeat itself with the National Broadband Plan.

As you could guess, the scale of the National Broadband Plan would be a confounding outlier in Granahan McCourt Capital's portfolio of investments.

Concerns about Granahan McCourt Capital (and enet), a member of the remaining consortium, serve striking relevance in the National Broadband Plan process. And failing to address these critical concerns before signing a contract would make a mockery of Ireland and its government.

Responding to an evolution of Market Conditions

As I highlighted earlier, it is important not to think about the National Broadband Plan in a vacuum. Make no mistake, its fortune will be very much influenced by external market conditions which fall outside the control of our government. These market conditions evolve at a rapid pace to meet the demands of consumers and to facilitate the introduction of new technologies.

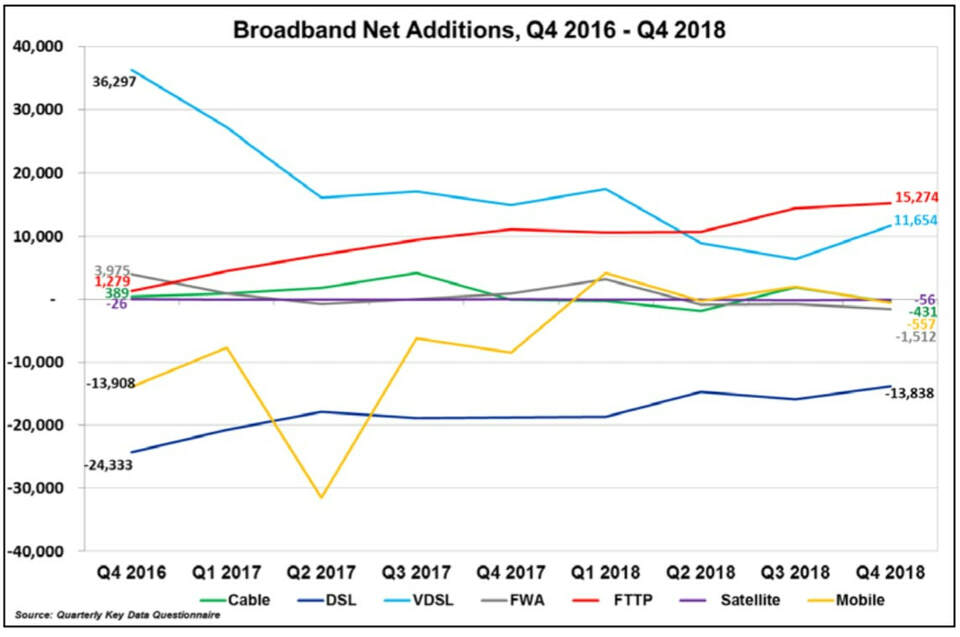

Currently, the most evident change in the market is a shift towards entirely new methods of delivering broadband, with a tectonic shift taking place in the realm of access networks. Let's not fluff the words, adoption of fibre at the edge is this change. And it's a change that should not be taken for granted because it catapults connectivity forward in every metric, setting the scene for the development of new applications and use cases that depend on its attributes.

You see, until recently, true end-to-end fibre products were only available to niche customers such as data centre owners, operators and large enterprises. With the extension of fibre from distribution networks such as the ESB's NTFON or enet's MANs to dense access networks, consumers can begin to enjoy the benefits of extremely low latency and scalable capacity.

Currently, the most evident change in the market is a shift towards entirely new methods of delivering broadband, with a tectonic shift taking place in the realm of access networks. Let's not fluff the words, adoption of fibre at the edge is this change. And it's a change that should not be taken for granted because it catapults connectivity forward in every metric, setting the scene for the development of new applications and use cases that depend on its attributes.

You see, until recently, true end-to-end fibre products were only available to niche customers such as data centre owners, operators and large enterprises. With the extension of fibre from distribution networks such as the ESB's NTFON or enet's MANs to dense access networks, consumers can begin to enjoy the benefits of extremely low latency and scalable capacity.

Commercial access deployments in the fixed market are now dependent on fibre, spearheaded by open eir and SIRO in Ireland. Data from ComReg shows that FTTH is the only broadband delivery method that experienced meaningful subscription growth in the last year, at an astonishing rate of 163.6%. Meanwhile, technically inferior networks such as DSL and satellite continue to experience a progressive decline of subscriptions.

This means putting strong contractual obligations and incentives in place for the winning bidder to upgrade the network and to invest in new, superior broadband delivery technologies as they are required.

The National Broadband Plan needs to move with the market to maintain its relevance for decades to come. This means putting strong contractual obligations and incentives in place for the winning bidder to upgrade the network and to invest in new, superior broadband delivery technologies as they are required. Without these guarantees, the longevity of our national broadband network will be inherently limited and not fit for purpose within a short space of time.

A Commercial Deployment Deep Dive

While I have touched on the severance of premises from the National Broadband Plan already, it is fitting that I return to it in greater detail amidst a flurry of ongoing and planned commercial investments in the expansion of fixed and wireless broadband services. The National Broadband Plan has yet to commence, as we painstakingly know, but its presence in the mind of the industry has acted as a catalyst for enhanced connectivity in Ireland.

This is vividly apparent in the fact that open eir has crisscrossed communities with fibre in a manner that prohibits state intervention and will force the government to access its network, at a cost.

Open eir's network is of particular interest to the outcome of the National Broadband Plan. Unfortunately, however, the wholesale operator has recognised this exact circumstance and leveraged the power of its monopoly to hamper plans for state intervention. This is vividly apparent in the fact that open eir has crisscrossed communities with fibre in a manner that prohibits state intervention and will force the government to access its network, at a cost.

Of course, expecting a private entity to be a pursuer of corporate social responsibility would be incredibly naive. But the level at which open eir has been permitted to redraw the state's intervention map and pass premises with fibre while refusing to connect them is just unacceptable.

Of course, expecting a private entity to be a pursuer of corporate social responsibility would be incredibly naive. But the level at which open eir has been permitted to redraw the state's intervention map and pass premises with fibre while refusing to connect them is just unacceptable.

The flawed, and some might say, not so impartial, regulatory oversight wielded by ComReg over open eir, an incumbent operator, has not helped Ireland's connectivity situation. Notably, ComReg gave the company the green light to raise the connection and migration charge on its wholesale FTTH network by 7,000% (from €2.50 to €170).

These charges apply to the network that will remove 335,000 cherry-picked homes from the catchment of state intervention. And, the consequences of such an extortionate, sudden increase in charges is obvious. ComReg has taken a move to strengthen open eir's monopoly, acting against consumers by creating an environment that will prompt an uptick in prices and a stagnation in competition amongst retailers.

These charges apply to the network that will remove 335,000 cherry-picked homes from the catchment of state intervention. And, the consequences of such an extortionate, sudden increase in charges is obvious. ComReg has taken a move to strengthen open eir's monopoly, acting against consumers by creating an environment that will prompt an uptick in prices and a stagnation in competition amongst retailers.

Its ratio of capital investment to revenues will continue to fall well below the industry average over the coming years, leaving much of Ireland's connectivity under the heal of a company that likens to an overused ATM: take out as much as you want without putting anything back in.

In urban Ireland, open eir has pledged to provide FTTH services to every town with more than 1,000 premises over the next five years. This means 1.4 million premises will bask in the glory of gigabit broadband, at a capital cost of €500 million to eir. On paper and through the carefully crafted press releases, the above would suggest there is an investment renaissance occurring within one of the world's most profitable incumbent operators.

The truth, as it transpires, is that eir's philosophy of under-investment in Irish infrastructure prevails. Its ratio of capital investment to revenues will continue to fall well below the industry average over the coming years, leaving much of Ireland's connectivity under the heal of a company that likens to an overused ATM: take out as much as you want without putting anything back in.

The truth, as it transpires, is that eir's philosophy of under-investment in Irish infrastructure prevails. Its ratio of capital investment to revenues will continue to fall well below the industry average over the coming years, leaving much of Ireland's connectivity under the heal of a company that likens to an overused ATM: take out as much as you want without putting anything back in.

It is also worth mentioning SIRO's increasingly integral role in Ireland's fixed market. As a pioneer of GPON and FTTH in Ireland, its fibre-centric vision has acted as a stepping stone for similar deployments by companies such as open eir. Of course, SIRO benefits tremendously from exclusive access to Ireland's electricity distribution network, setting it on a path to cover over 500,000 urban and suburban premises with FTTH.

Over at Imagine, Ireland's largest wireless broadband provider, a major network expansion in the 3.6GHz band is underway. The company's portfolio of 60MHz within the band means it will be able to provide a service capable of 150Mbps to 400,000 of the premises that are earmarked for state intervention.

Over at Imagine, Ireland's largest wireless broadband provider, a major network expansion in the 3.6GHz band is underway. The company's portfolio of 60MHz within the band means it will be able to provide a service capable of 150Mbps to 400,000 of the premises that are earmarked for state intervention.

However, while Imagine won't tell you this, I will: its wireless solution is no replacement for a fixed-based National Broadband Plan, and those who think it is are living in la la land where considerations about capacity and the density of the site grid do not exist.

The detailed commercial deployments represent momentous milestone's in Ireland's quest for enhanced connectivity. However, they fail to address the digital divide between urban and rural Ireland, and in many cases, exacerbate it. This should be a clear-cut example of where commercial investment is viable and where it isn't, and how the National Broadband Plan is required to patch these gaps.

The detailed commercial deployments represent momentous milestone's in Ireland's quest for enhanced connectivity. However, they fail to address the digital divide between urban and rural Ireland, and in many cases, exacerbate it. This should be a clear-cut example of where commercial investment is viable and where it isn't, and how the National Broadband Plan is required to patch these gaps.

Trouble is in the air at 3.6GHz

Wireless solutions have been viewed as something of a quick fix in the National Broadband Plan process, with mindless debates alluding to the superiority of a broadband delivery system that utilises radio spectrum. While it has been said before, I'll say it again: no existing wireless solution at our disposal meets the same performance criteria as fixed fibre does. There is an intrinsic limit to the longevity of every wireless network.

The National Broadband Plan is a long-term project, and so the operational expenses involved are just as important to consider as the upfront capital investment required.

It is key to think of Fixed Wireless Access as a means to complement the National Broadband Plan, not to replace it. Sure, from a capital investment standpoint, FWA is less expensive than fibre, but the opposite is true for operational expenses. This is something that many have missed. The National Broadband Plan is a long-term project, and so the operational expenses involved are just as important to consider as the upfront capital investment required.

We are at the beginning of another transformation in wireless, thanks to 5G NR. But its portfolio of benefits is misunderstood and has fallen victim to an unprecedented level of hype. Sub-6GHz 5G NR will be most relevant to Ireland in the coming years because it offers a meaningful capacity uplift while maintaining similar propagation characteristics (when Massive MIMO is implemented).

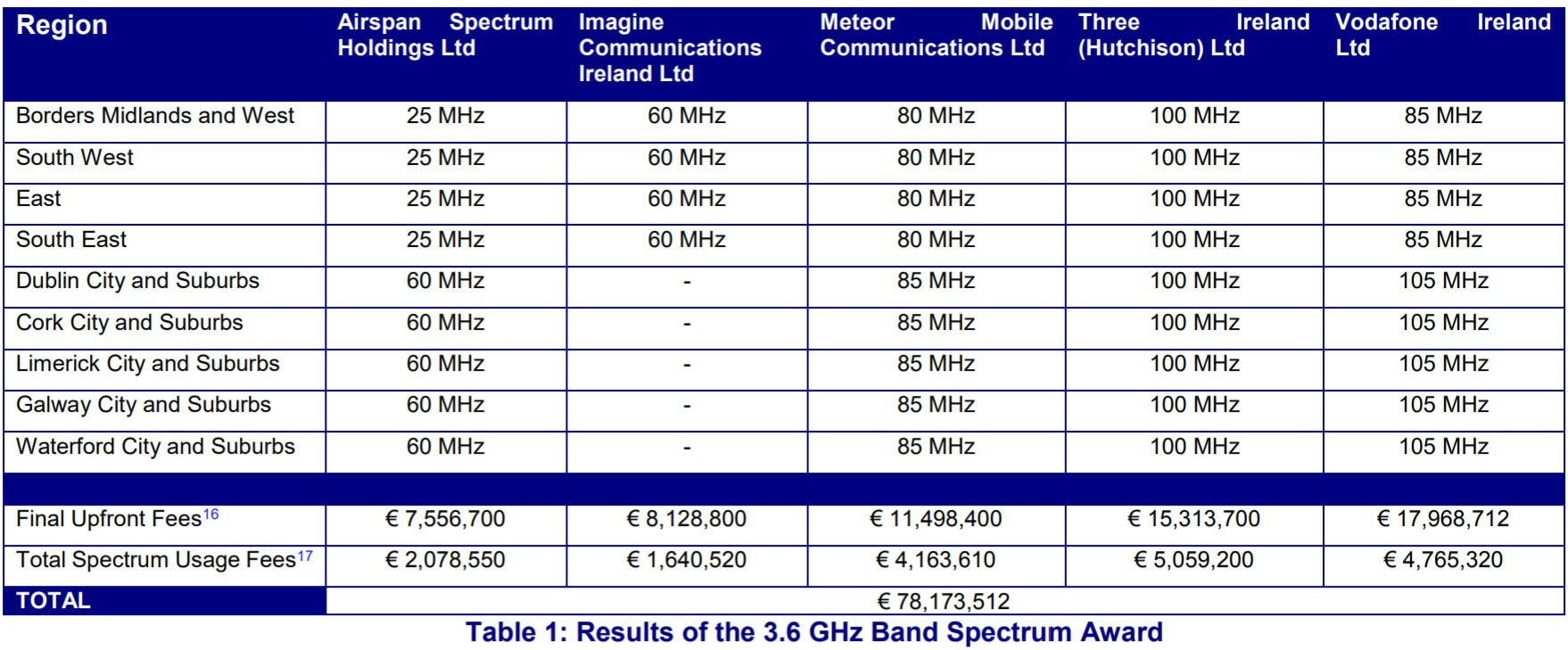

In 2017, ComReg assigned 350MHz of TDD spectrum in the 3.6GHz band to Ireland's operators, at an upfront cost of €60.5m. But, things have not gone to plan since then and the process of transitioning the spectrum from legacy use cases and liberalising it for 5G NR has been absurdly slow. This will have a direct impediment on the deployment of 5G NR in Ireland, and if it is not addressed as a matter of urgency, Ireland will be left behind in yet another connectivity race.

Vodafone, in particular, is worst affected by the transition process. Its 3.6GHz band license has commenced in all blocks in Dublin (105MHz) and the South East (85MHz), with every other region awaiting liberalisation. This means Vodafone cannot proceed with a national deployment strategy for sub-6GHz 5G NR. Can you imagine the ferocity at which alarm bells are ringing within Big Red?

At Three, the 3.6GHz situation is less bleak, with all blocks of the spectrum live in the South West, East, Dublin, Cork and Galway regions. This puts Three in a better position to embark on a widespread 3.6GHz deployment in Ireland, and combined with its existing spectrum portfolio, which is the largest of any operator, we can expect to see major performance gains after launch.

In 2017, ComReg assigned 350MHz of TDD spectrum in the 3.6GHz band to Ireland's operators, at an upfront cost of €60.5m. But, things have not gone to plan since then and the process of transitioning the spectrum from legacy use cases and liberalising it for 5G NR has been absurdly slow. This will have a direct impediment on the deployment of 5G NR in Ireland, and if it is not addressed as a matter of urgency, Ireland will be left behind in yet another connectivity race.

Vodafone, in particular, is worst affected by the transition process. Its 3.6GHz band license has commenced in all blocks in Dublin (105MHz) and the South East (85MHz), with every other region awaiting liberalisation. This means Vodafone cannot proceed with a national deployment strategy for sub-6GHz 5G NR. Can you imagine the ferocity at which alarm bells are ringing within Big Red?

At Three, the 3.6GHz situation is less bleak, with all blocks of the spectrum live in the South West, East, Dublin, Cork and Galway regions. This puts Three in a better position to embark on a widespread 3.6GHz deployment in Ireland, and combined with its existing spectrum portfolio, which is the largest of any operator, we can expect to see major performance gains after launch.

For eir, liberalisation of its 3.6GHz assignment is limited to the Borders, Midlands, West and East region. Eir's 3.6GHz portfolio is the smallest of Ireland's three operators, with 80MHz in four rural regions and 85MHz in five urban regions. Data shows that its mobile network is the least performant in Ireland, suffering from limited availability of carrier aggregation in congestion-stricken urban and suburban areas.

These delays in liberalisation of the 3.6GHz band can be attributed to a failure of transition licensees to vacate the spectrum in their transition service areas (20km radius). There are over 20,000 customers that actively access FWA services in the 3.6GHz band, many of them being customers of Imagine. Out of its 241 transition service areas, Imagine has only vacated 46.

Upon request for documentation from ComReg, LukeKehoe.com has learned of further license holders in the 3.6GHz band which have yet to vacate the spectrum. These include Airpseed (owned by Granahan McCourt Capital), permaNET, Ripplecom and Lightnet. Further details about the transition service areas can be viewed here.

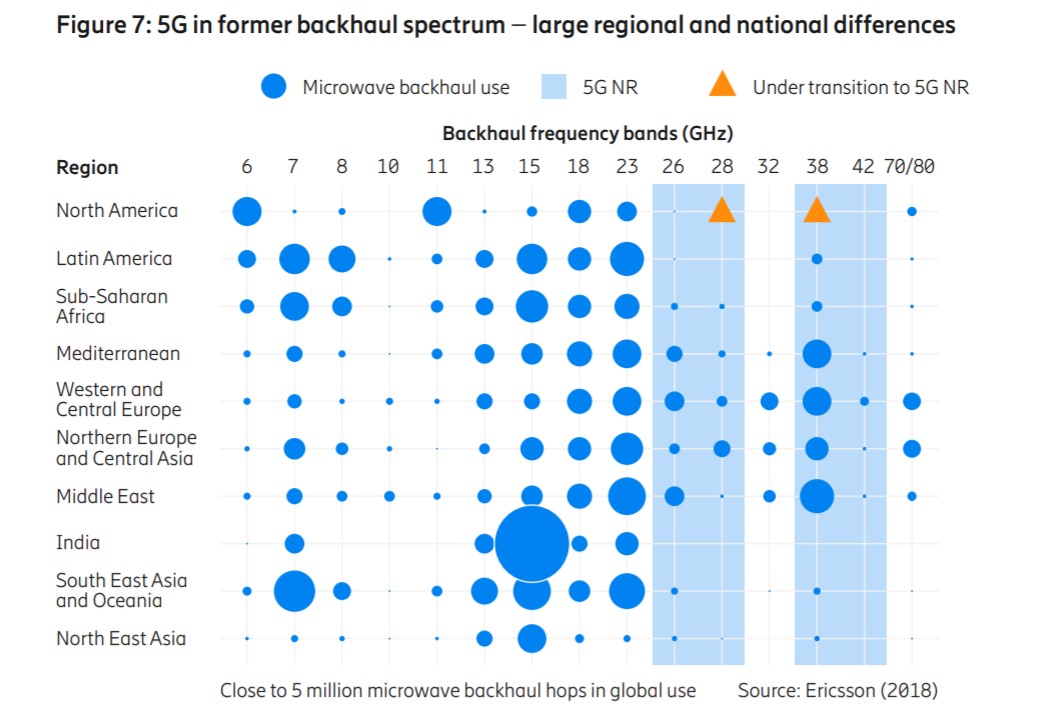

The shift to mmWave spectrum will be an incredibly complex process, heightened by the fact that Ireland is a land of soaring hills and majestic valleys with a dispersed population. ComReg has yet to release mmWave spectrum for access use, with the 26GHz band limited to microwave backhauling. Industry trends in Europe would point to the 26GHz and 42GHz bands becoming the go-to for mmWave access use, with microwave likely to be shifted to 32GHz and the E-Band.

These delays in liberalisation of the 3.6GHz band can be attributed to a failure of transition licensees to vacate the spectrum in their transition service areas (20km radius). There are over 20,000 customers that actively access FWA services in the 3.6GHz band, many of them being customers of Imagine. Out of its 241 transition service areas, Imagine has only vacated 46.

Upon request for documentation from ComReg, LukeKehoe.com has learned of further license holders in the 3.6GHz band which have yet to vacate the spectrum. These include Airpseed (owned by Granahan McCourt Capital), permaNET, Ripplecom and Lightnet. Further details about the transition service areas can be viewed here.

The shift to mmWave spectrum will be an incredibly complex process, heightened by the fact that Ireland is a land of soaring hills and majestic valleys with a dispersed population. ComReg has yet to release mmWave spectrum for access use, with the 26GHz band limited to microwave backhauling. Industry trends in Europe would point to the 26GHz and 42GHz bands becoming the go-to for mmWave access use, with microwave likely to be shifted to 32GHz and the E-Band.

Conclusion: Executing the Formula

Even as the day of judgement for the future of connectivity on this island looms, the bevvy of questions outweighs a sparse set of answers. That's a perilous precedent for Ireland and one which will etch its way into our history for all the wrong reasons. We cannot allow the political rush for short-term gain to disrupt a plan that will transform the fabric of Irish society for generations to come.

Contrasting the mesmerising tectonic shift created in the wake of electrification with the introduction of universal high-speed broadband is one of the few ways to convey the enormous potential of the National Broadband Plan. Mark my words, a successful project will give Ireland and its people so much in return, with the budget allocation destined to become a distant memory.

Contrasting the mesmerising tectonic shift created in the wake of electrification with the introduction of universal high-speed broadband is one of the few ways to convey the enormous potential of the National Broadband Plan. Mark my words, a successful project will give Ireland and its people so much in return, with the budget allocation destined to become a distant memory.

Contrasting the mesmerising tectonic shift created in the wake of electrification with the introduction of universal high-speed broadband is one of the few ways to convey the enormous potential of the National Broadband Plan.

There is a formula for successful, state-subsidised infrastructure projects. Ireland has executed it in the past, and now we just need to apply it to a greater problem: the digital divide. Ending the visceral disconnect between the government, the industry and the people on the ground that will ultimately make this project possible is the best place to start.

From there, we can swallow the price-tag, which will be spread across multiple decades, and work to put strong contractual obligations and regulatory oversight in place such that a future-proof wholesale, open access network delivers on its fundamental promise to connect the disconnected in Ireland.

Because, remember, kicking the connectivity can down the road is an effective middle finger to rural Ireland.

From there, we can swallow the price-tag, which will be spread across multiple decades, and work to put strong contractual obligations and regulatory oversight in place such that a future-proof wholesale, open access network delivers on its fundamental promise to connect the disconnected in Ireland.

Because, remember, kicking the connectivity can down the road is an effective middle finger to rural Ireland.

How Fibre is shaping 5GThe future of a wireless ecosystem hinges on fibre, pixie dust in Ireland.

|