Mobile Coverage and Ireland: Not a Match

Cost and coverage teeter on a delicate balance, and Ireland's scales is particularly sensitive.

Published 06/12/18

In the midst of a sustained effort to undermine the fundamental role which fibre must play in our telecoms infrastructure, present and future, new data has emerged which further conveys the distasteful message that providing quality broadband to every person on the island of Ireland is damn-expensive, and even a wireless approach will leave our wallets praying for mercy.

To sum it up, ComReg has finally shone a light on something that has been glorified beyond relation, mobile broadband, and more specifically, the cost of providing a ubiquitous service on an island of soaring hills, mindbogglingly long cul-de-sacs and eerily remote farmhouses. The topography and population distribution in Ireland have left us juggling between different broadband deployment strategies, and the release of informative reports by the telecoms regulator which put facts first help to bring clarity to a very stark situation.

With three mobile providers battling one another in one of the most competitive mobile markets on the continent, one could only assume that a foray of this battle exists in mobile coverage. Sadly, ComReg has concluded that achieving pervasive, high-speed (above 30Mbps) mobile coverage in Ireland within our lifetime is not possible without state intervention, and the question now asks whether intervention is actually logical.

Mobile providers such as Three and Vodafone can only provide a very finite level of population coverage before any further expansion is deemed not commercially viable, and we are rapidly approaching that level with 4G. Looking to 5G, achieving nationwide coverage in the mmWave bands would seem absurd today, with coverage escaping from urban centres in its initial years of deployment likely to be a rare occasion. This contradicts the belief that 5G (in the high-frequency bands), or any mobile network for that matter, can solve our broadband woes.

To sum it up, ComReg has finally shone a light on something that has been glorified beyond relation, mobile broadband, and more specifically, the cost of providing a ubiquitous service on an island of soaring hills, mindbogglingly long cul-de-sacs and eerily remote farmhouses. The topography and population distribution in Ireland have left us juggling between different broadband deployment strategies, and the release of informative reports by the telecoms regulator which put facts first help to bring clarity to a very stark situation.

With three mobile providers battling one another in one of the most competitive mobile markets on the continent, one could only assume that a foray of this battle exists in mobile coverage. Sadly, ComReg has concluded that achieving pervasive, high-speed (above 30Mbps) mobile coverage in Ireland within our lifetime is not possible without state intervention, and the question now asks whether intervention is actually logical.

Mobile providers such as Three and Vodafone can only provide a very finite level of population coverage before any further expansion is deemed not commercially viable, and we are rapidly approaching that level with 4G. Looking to 5G, achieving nationwide coverage in the mmWave bands would seem absurd today, with coverage escaping from urban centres in its initial years of deployment likely to be a rare occasion. This contradicts the belief that 5G (in the high-frequency bands), or any mobile network for that matter, can solve our broadband woes.

The Facts: Scarily Expensive with a Scarily Short Lifespan

Let's get this out of the way before I unleash a deluge of facts on you. Providing mobile coverage in Ireland that serves the entirety of our population is significantly less expensive than embarking on the same approach with fibre. However, there are two fundamental issues with this wireless approach. For one, the lifespan of such a network is forever terminal, with wireless networks being deployed today set to be rendered obsolete in just under a decade and replaced all over again. The other issue centres around the fact, not some crazy opinion or thought, that a high-speed wireless network in Ireland will require the deployment of fibre infrastructure to thousands of new radio sites across the country, something which will drive the cost up by orders of magnitude. There are other drawbacks too, with fragmentation in the 5G space already proving to be a pain point for advanced wireless broadband deployments.

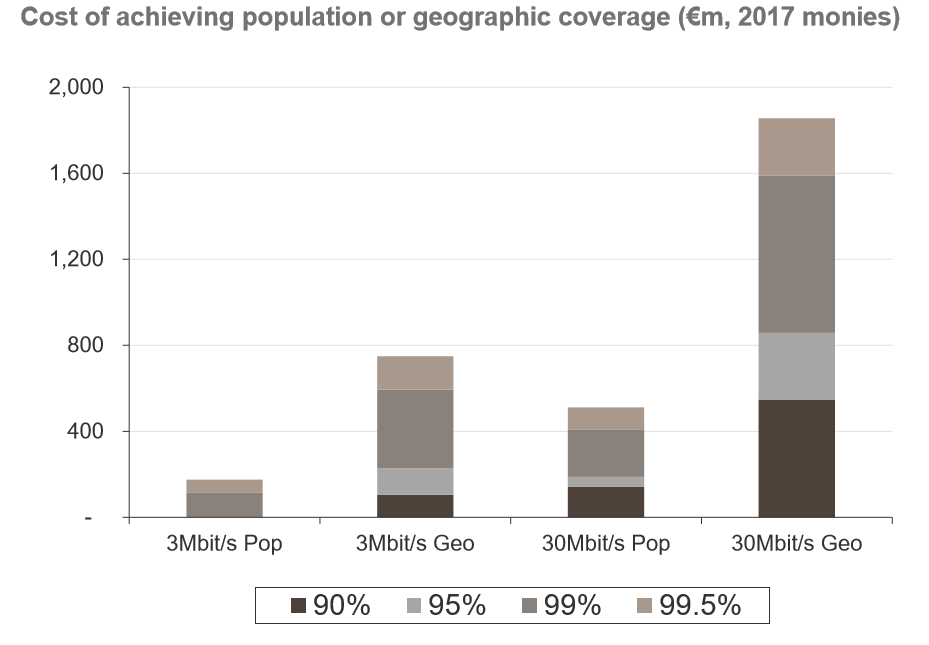

In a report commissioned by ComReg, titled the "Future of Mobile Connectivity in Ireland", the watchdog considers the costs associated with deploying mobile networks on this island. Covering 99.5% of the Irish landmass with a RAN supporting an average speed of 30Mbps would cost €4,250 per person and take decades to complete, translating to a capex requirement of €1.86 billion. Putting it into context, the build-out of this network could be complete after 2070 according to ComReg, by which time 30Mbps will be wholly unsuitable for the bandwidth requirements of the time. Essentially, the network would be dead on arrival. Achieving the same level of coverage based on a population approach would be almost five times less expensive and could be achieved before 2043.

In a report commissioned by ComReg, titled the "Future of Mobile Connectivity in Ireland", the watchdog considers the costs associated with deploying mobile networks on this island. Covering 99.5% of the Irish landmass with a RAN supporting an average speed of 30Mbps would cost €4,250 per person and take decades to complete, translating to a capex requirement of €1.86 billion. Putting it into context, the build-out of this network could be complete after 2070 according to ComReg, by which time 30Mbps will be wholly unsuitable for the bandwidth requirements of the time. Essentially, the network would be dead on arrival. Achieving the same level of coverage based on a population approach would be almost five times less expensive and could be achieved before 2043.

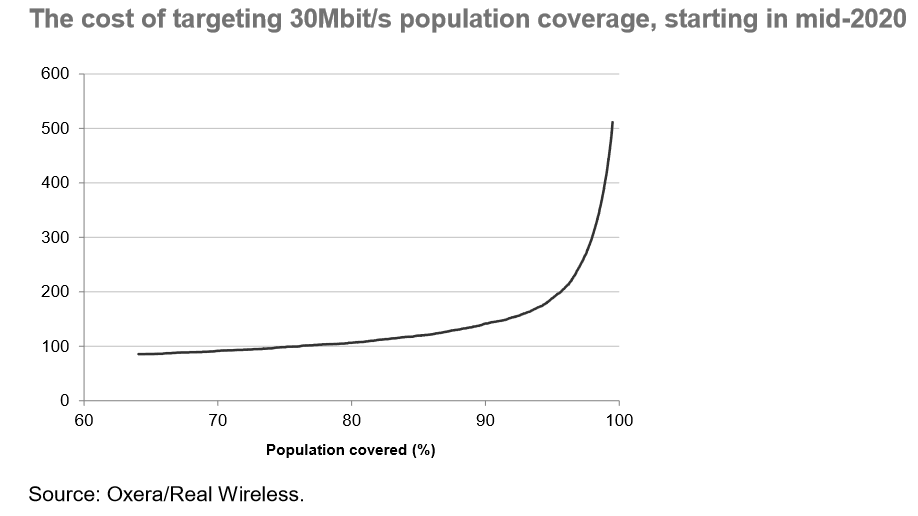

The above brings to light the fact that geographic coverage and population coverage are very different (take note eir), both in terms of the literal meaning and the investment required to achieve high levels of coverage with either. ComReg estimates that the investment required to achieve population coverage (30Mbps) beyond 95% rises exponentially and is not likely to be commercially viable for providers before 2027 without state intervention. For example, the estimated cost of increasing 30Mbps population coverage from 99.0% to 99.5% is €102m. These figures help to explain recent stagnation in the expansion of our 4G networks, which now boast population coverage (note that there is no bandwidth threshold) in excess of 96%, but have failed to expand much further.

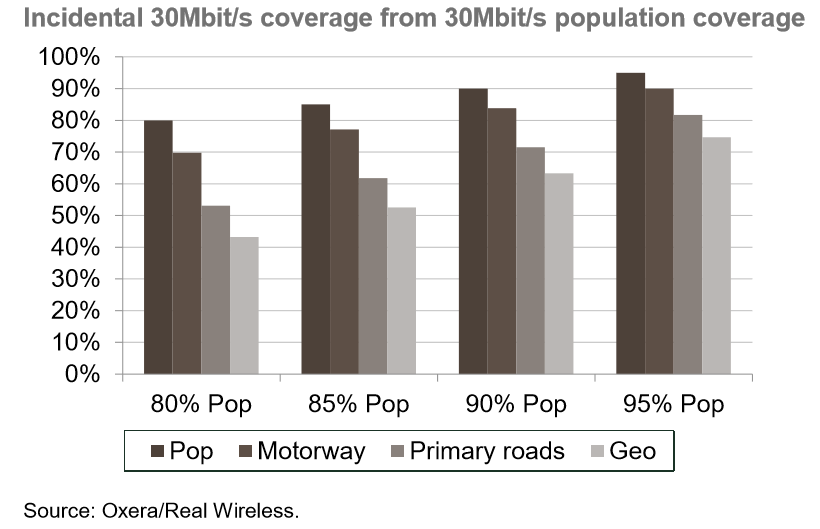

An incredibly intriguing discovery by ComReg is the proportional link between population coverage and geographic coverage, along with coverage on Motorways and National primary roads. If population coverage is 90%, incidental geographic coverage would be 60%, while coverage on Motorways would be close to 80% and National primary roads just above 70%. These statistics are dictated by the distribution of Ireland's population, and the density of our road infrastructure. When a provider such as Vodafone sets out a deployment strategy to reach a specific level of population coverage, the level of geographic and road coverage will reach a level which is proportionate to where the population presides, because as we know, roads only exist where people do.

As explained earlier, the cost curve disparity results in any capex requirement rising exponentially above 95% population coverage, and the same is true with in-vehicle road coverage. However, road coverage is less costly to achieve than population coverage. That last point is likely to continue as ducting is being installed in the construction stages of new roads, making it easier for the deployment of dark fibre which can be used for fixed backhaul from new or existing radio sites.

An incredibly intriguing discovery by ComReg is the proportional link between population coverage and geographic coverage, along with coverage on Motorways and National primary roads. If population coverage is 90%, incidental geographic coverage would be 60%, while coverage on Motorways would be close to 80% and National primary roads just above 70%. These statistics are dictated by the distribution of Ireland's population, and the density of our road infrastructure. When a provider such as Vodafone sets out a deployment strategy to reach a specific level of population coverage, the level of geographic and road coverage will reach a level which is proportionate to where the population presides, because as we know, roads only exist where people do.

As explained earlier, the cost curve disparity results in any capex requirement rising exponentially above 95% population coverage, and the same is true with in-vehicle road coverage. However, road coverage is less costly to achieve than population coverage. That last point is likely to continue as ducting is being installed in the construction stages of new roads, making it easier for the deployment of dark fibre which can be used for fixed backhaul from new or existing radio sites.

Providing coverage on both Motorways and National primary roads is considerably more expensive than focusing solely on Motorways. As an example, the cost of covering Motorways alone with 99.5% 30Mbps coverage equals €160m, but adding National primary roads rises this sharply to €283m.

Finally, a critical point that must be stressed, the cost of providing coverage varies wildly depending on the average speed target, which has been 30Mbps in the above data. The reasons for this are pretty obvious. For a mobile provider to achieve high speeds consistently there is a need to deploy higher frequency spectrum such as the 1800MHz band, which has the resulting impact of a smaller coverage footprint. Alternatively, carrier aggregation can be utilised to aggregate low bands with high bands (Vodafone is currently aggregating 20MHz of 1800MHz with 10MHz of 800MHz) as an effort to boost capacity. The difference in cost between providing 99.5% population coverage at 3Mbps and 30Mbps is €123m.

Finally, a critical point that must be stressed, the cost of providing coverage varies wildly depending on the average speed target, which has been 30Mbps in the above data. The reasons for this are pretty obvious. For a mobile provider to achieve high speeds consistently there is a need to deploy higher frequency spectrum such as the 1800MHz band, which has the resulting impact of a smaller coverage footprint. Alternatively, carrier aggregation can be utilised to aggregate low bands with high bands (Vodafone is currently aggregating 20MHz of 1800MHz with 10MHz of 800MHz) as an effort to boost capacity. The difference in cost between providing 99.5% population coverage at 3Mbps and 30Mbps is €123m.

Network Sharing Agreements: A Frayed Past

In a perfect world, there would be seamless sharing of network assets between mobile providers to lower their capex and opex, while maintaining a quality experience on the RAN for customers. As you might expect, network sharing is complex, and it can raise some serious eyebrows from the companies which are not involved in such an agreement. Ireland has had a frayed relationship with network sharing agreements from the very beginning, so much so that we are now entering uncharted territory, in which no mobile provider is in engaged in a sharing agreement with their competitor.

Mosaic, a sharing agreement that Three and eir entered before the merger with Telefónica's O2 and was later renewed by the EU Commission under competition guidelines, is now going the way of the dinosaur. The same occurred with Netshare, which saw Three reaching for support from Vodafone's more developed network.

Here's the problem with network sharing agreements: they don't last. Everyone acknowledges the fact that the telecoms market is a fast-paced and ever-evolving land of change and innovation. There has been a failure to devise sharing agreements which can survive a transition between wireless standards. These agreements are signed in the early deployment stages of a new standard, after which, the incentive for the agreement to continue diminishes for all of the parties involved.

Another negative impact of network sharing agreements is the resulting dependency of one network on another. This was a major cause of concern with Three before its merger with O2, as the company held no spectrum that it could use for widespread 2G voice and text coverage, leaving the company completely reliant on Vodafone for this services. For consumers, this decreases the level of choice available and increases the severity of outages when they inevitably prop up.

It is for these reasons that suggesting the construction of a shared wireless network to form part or all of the National Broadband Plan would be ill-fated. This is a long-term plan which cannot afford to be torn up within the first few years of deployment or fall victim to the diverging interests of parties participating in a sharing agreement.

Mosaic, a sharing agreement that Three and eir entered before the merger with Telefónica's O2 and was later renewed by the EU Commission under competition guidelines, is now going the way of the dinosaur. The same occurred with Netshare, which saw Three reaching for support from Vodafone's more developed network.

Here's the problem with network sharing agreements: they don't last. Everyone acknowledges the fact that the telecoms market is a fast-paced and ever-evolving land of change and innovation. There has been a failure to devise sharing agreements which can survive a transition between wireless standards. These agreements are signed in the early deployment stages of a new standard, after which, the incentive for the agreement to continue diminishes for all of the parties involved.

Another negative impact of network sharing agreements is the resulting dependency of one network on another. This was a major cause of concern with Three before its merger with O2, as the company held no spectrum that it could use for widespread 2G voice and text coverage, leaving the company completely reliant on Vodafone for this services. For consumers, this decreases the level of choice available and increases the severity of outages when they inevitably prop up.

It is for these reasons that suggesting the construction of a shared wireless network to form part or all of the National Broadband Plan would be ill-fated. This is a long-term plan which cannot afford to be torn up within the first few years of deployment or fall victim to the diverging interests of parties participating in a sharing agreement.

The Case for Geographic Coverage Obligations

Those left in the dark by mobile providers are begging for a transition from population coverage to geographic coverage statistics being cited by Irish mobile providers. In this report, ComReg considers such a transition to an effort based on achieving ubiquitous geographic coverage nonsensical because of the ghastly costs associated (€4,250 per person).

This conclusion will have a major impact on how mobile providers are told to make use of their spectrum, with population coverage obligations already in place across the board. These obligations should be focused primarily where people live, but also consider where people work, transit and commute, and places of interest.

Moreover, as detailed earlier, the level of population coverage that is targeted is proportionate to geographic coverage. There will be some happy to trumpet the idea that omnipresent geographic coverage is not necessary anyway, but that argument quickly becomes irrelevant if we are to utilise a wireless approach to the National Broadband Plan, a plan which does not pick and choose which areas are to receive service based on commercial viability.

Introducing geographic coverage obligations within future spectrum auctions, especially those in the high-bands, would trigger unnecessary burdens for mobile providers and may hamper their ability to shape the design of the network in a way that achieves a balance between coverage and capacity.

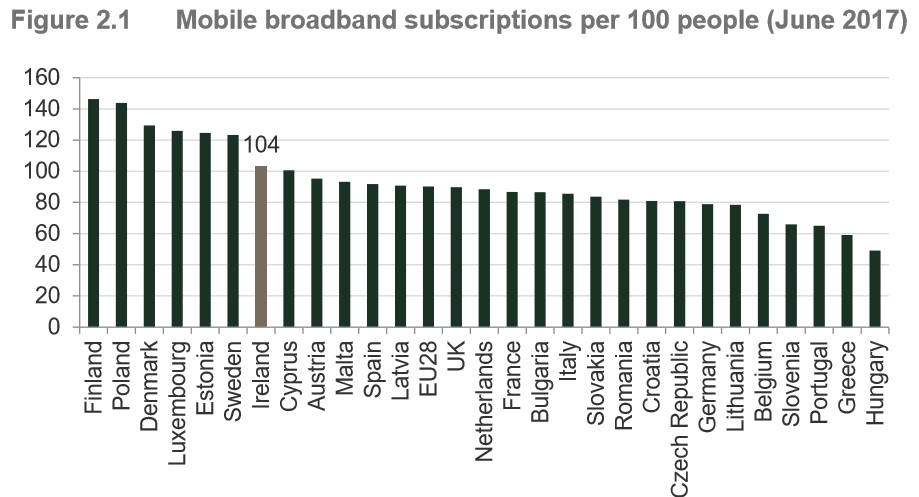

There is a credible possibility for allocating low-bands such as the upcoming 700MHz release next year with a geographic coverage obligation. This would balance costs for the mobile provider and coverage for the regulator, something that has failed to present itself with the current population coverage system. Such a move would also work to end tactical collusion amongst mobile providers in the Irish market, a dirty secret which was proven to be true during the reign of O2 and Vodafone's duopoly. And, as you can see in the graph portrayed above, Irish consumers are some of the most prolific mobile broadband customers in Europe, highlighting the need for radical change in the way that we allocate spectrum.

This conclusion will have a major impact on how mobile providers are told to make use of their spectrum, with population coverage obligations already in place across the board. These obligations should be focused primarily where people live, but also consider where people work, transit and commute, and places of interest.

Moreover, as detailed earlier, the level of population coverage that is targeted is proportionate to geographic coverage. There will be some happy to trumpet the idea that omnipresent geographic coverage is not necessary anyway, but that argument quickly becomes irrelevant if we are to utilise a wireless approach to the National Broadband Plan, a plan which does not pick and choose which areas are to receive service based on commercial viability.

Introducing geographic coverage obligations within future spectrum auctions, especially those in the high-bands, would trigger unnecessary burdens for mobile providers and may hamper their ability to shape the design of the network in a way that achieves a balance between coverage and capacity.

There is a credible possibility for allocating low-bands such as the upcoming 700MHz release next year with a geographic coverage obligation. This would balance costs for the mobile provider and coverage for the regulator, something that has failed to present itself with the current population coverage system. Such a move would also work to end tactical collusion amongst mobile providers in the Irish market, a dirty secret which was proven to be true during the reign of O2 and Vodafone's duopoly. And, as you can see in the graph portrayed above, Irish consumers are some of the most prolific mobile broadband customers in Europe, highlighting the need for radical change in the way that we allocate spectrum.

Synthetic Network Model

ComReg devised a synthetic network model to calculate the cost of establishing a new mobile network in Ireland, from scratch. This would appear the only remaining approach for a National Broadband Plan powered by a wireless solution that does not incorporate some form of network sharing agreement.

As you would expect, the investment requirements to provide omnipresent coverage are simply incredible, and need I repeat, not commercially viable in the short, medium or even long term without state intervention. For example, even if every mobile provider in Ireland came together with their radio site assets, the resulting level of geographic coverage would still fall well below what one could call ubiquitous 30Mbps coverage.

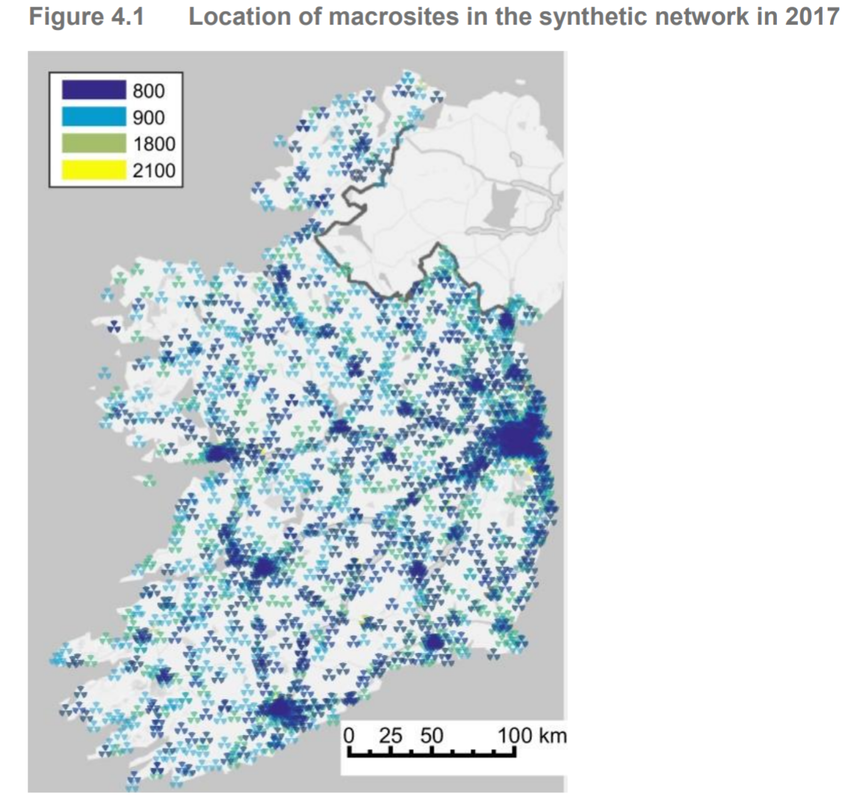

This synthetic network operates in the four available bands that are utilised by mobile providers today. The low bands include 800MHz 4G (870 sites), which has become the go-to spectrum for rural 4G deployment because of its large coverage footprint, and 900MHz 2G/3G (1,890 sites), which is available extensively to ensure the 3G HD Voice experience is consistent across large swathes of our Motorways and National primary roads.

On the higher end of the spectrum, the synthetic network makes use of 1800MHz (595 sites) for high-capacity urban coverage. The 2100MHz band (1,500 sites) has yet to be liberalised by ComReg, and this band is used for high-capacity 3G deployments in urban centres. However, for the purpose of this model, the synthetic network does not implement carrier aggregation, which does lead to enhanced performance at the cell edge.

As you would expect, the investment requirements to provide omnipresent coverage are simply incredible, and need I repeat, not commercially viable in the short, medium or even long term without state intervention. For example, even if every mobile provider in Ireland came together with their radio site assets, the resulting level of geographic coverage would still fall well below what one could call ubiquitous 30Mbps coverage.

This synthetic network operates in the four available bands that are utilised by mobile providers today. The low bands include 800MHz 4G (870 sites), which has become the go-to spectrum for rural 4G deployment because of its large coverage footprint, and 900MHz 2G/3G (1,890 sites), which is available extensively to ensure the 3G HD Voice experience is consistent across large swathes of our Motorways and National primary roads.

On the higher end of the spectrum, the synthetic network makes use of 1800MHz (595 sites) for high-capacity urban coverage. The 2100MHz band (1,500 sites) has yet to be liberalised by ComReg, and this band is used for high-capacity 3G deployments in urban centres. However, for the purpose of this model, the synthetic network does not implement carrier aggregation, which does lead to enhanced performance at the cell edge.

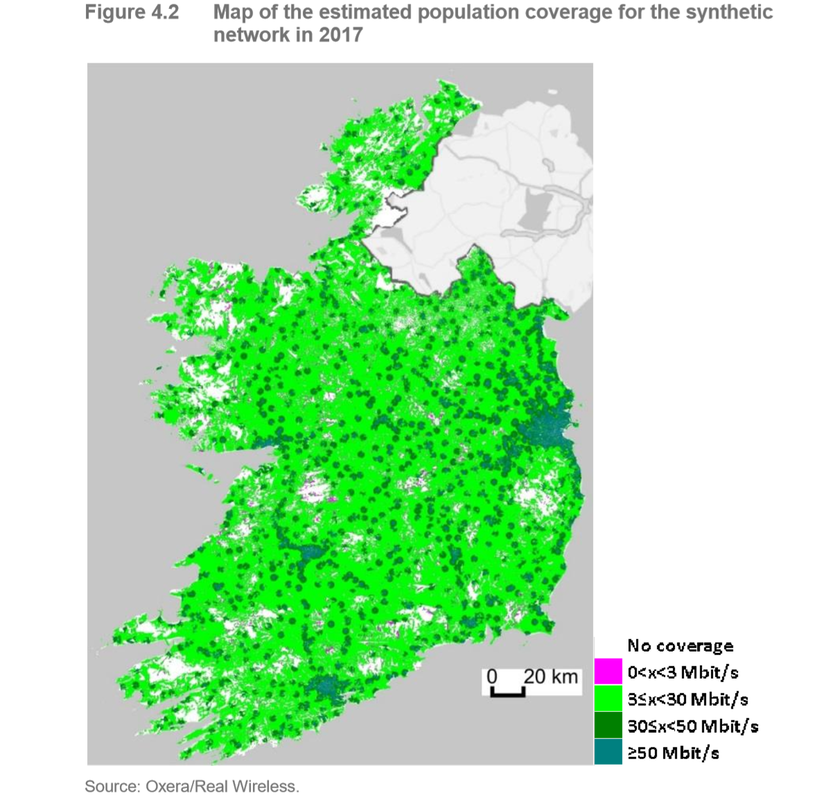

The results of the synthetic network model will be confounding for those that believe high levels of coverage can be achieved with a small radio site portfolio. Population coverage would stand at 62.4% (30Mbps), with geographic coverage shockingly poor at 18.3% (30Mbps). If that same RAN is required to provide speeds of above 50Mbps, population coverage would crash to 43.6% while geographic coverage would fall to just 6.3%.

These are insightful statistics, whether we like them or not, and they speak to the wider challenge facing mobile providers in Ireland: determining a balance between coverage, capacity and commercial viability. Such challenges will always exist in the absence of state intervention, and therefore, it is not logical to expect universal coverage being provided by any network today.

Perhaps, even more intriguing, is the data which refers to the coverage of this synthetic network along Ireland's railways and roads. There is a huge discrepancy between the availability of coverage on railways and roads in Ireland, both in this network model and in reality. This can be explained by the presence of radio sites at multiple intervals along railway lines. As detailed, fixed backhaul plays an integral role in the makeup of the core network, and BT operates extensive dark fibre infrastructure along Ireland's railways.

These are insightful statistics, whether we like them or not, and they speak to the wider challenge facing mobile providers in Ireland: determining a balance between coverage, capacity and commercial viability. Such challenges will always exist in the absence of state intervention, and therefore, it is not logical to expect universal coverage being provided by any network today.

Perhaps, even more intriguing, is the data which refers to the coverage of this synthetic network along Ireland's railways and roads. There is a huge discrepancy between the availability of coverage on railways and roads in Ireland, both in this network model and in reality. This can be explained by the presence of radio sites at multiple intervals along railway lines. As detailed, fixed backhaul plays an integral role in the makeup of the core network, and BT operates extensive dark fibre infrastructure along Ireland's railways.

As such, radio sites which preside along the rail system can access inexpensive fixed backhaul from a wholesale provider, something which is not the case along our roads. The lack of fixed infrastructure along roads forces mobile providers to make use of microwave backhaul, which is very effective for rural sites, but offers inferior performance thanks to the physics of radio spectrum. The alternative option is to deploy fibre to the site (FTTA), a very costly approach on a scale of thousands of radio sites.

With the site portfolio of the synthetic network, coverage availability at 30Mbps is almost twice that on railways (61.7%) compared to both National primary roads (31.3%) and on National secondary roads (30.1%). The situation is even starker when a 50Mbps threshold is used for coverage, with railways enjoying a superior 30.3% availability compared to 23.9% on motorways, 12.3% on National primary roads and 14.6% on National secondary roads. This level of coverage is not acceptable, and the lack of fixed backhaul along roads continues to deter mobile providers from deploying more radio sites in these regions.

As such, radio sites which preside along the rail system can access inexpensive fixed backhaul from a wholesale provider, something which is not the case along our roads. The lack of fixed infrastructure along roads forces mobile providers to make use of microwave backhaul, which is very effective for rural sites, but offers inferior performance thanks to the physics of radio spectrum. The alternative option is to deploy fibre to the site (FTTA), a very costly approach on a scale of thousands of radio sites.

With the site portfolio of the synthetic network, coverage availability at 30Mbps is almost twice that on railways (61.7%) compared to both National primary roads (31.3%) and on National secondary roads (30.1%). The situation is even starker when a 50Mbps threshold is used for coverage, with railways enjoying a superior 30.3% availability compared to 23.9% on motorways, 12.3% on National primary roads and 14.6% on National secondary roads. This level of coverage is not acceptable, and the lack of fixed backhaul along roads continues to deter mobile providers from deploying more radio sites in these regions.

Wireless is not viable without a Reformation

Mobile has a role to play in the vision to provide high-speed broadband to every person on the island of Ireland, and those that disregard this approach for its inferior capacity compared to fibre are failing to look to at the advantages of the technology, of which there are many. However, cost and coverage teeter on a delicate balance, and Ireland's scales is particularly sensitive. Any wireless solution that is deployed today will have a shorter lifespan than its fixed fibre alternatives, and with the cost of providing fibre all the way to the home rapidly plunging, the viability of wireless is rendered a short-term resolution to a very long-term problem.

Wireless brings many strings with it, strings which ultimately decide the future of rural Ireland and its very existence. Fragmentation is a string, and so too is the enormous cost to provide ubiquitous, future-proof coverage in a country where 76% of the land is occupied by farms and forests and where 3% of the population lives in 28% of the land area. The question is, how many strings are we willing to endure? Mobile providers have already met a glass ceiling, with further expansion being deemed not commercially viable.

Some would even argue that the demand for coverage is beginning to overtake the demand for capacity once again in many locations as the pervasiveness of high-speed fixed connections allows providers to shift traffic away from the RAN. In my eyes, the most astonishing revelation in ComReg's report is the conclusion that achieving ubiquitous mobile coverage in Ireland is not possible before 2070 without state intervention. If this is the case, we might not live to witness the end of the rural/urban digital divide in Ireland, and that creates a sincere sense of sadness within me. This is a massive alarm bell, a bell which will only scream louder as 5G becomes available in cities and towns, not rural villages and farms.

We need drastic and immediate action to solve the rural/urban digital divide before it is too late, and regardless of how aggressively we lobby our mobile providers to take action, the activation of a magic wand to solve all of our problems is not possible. Only the expansion of fibre distribution networks, increase in the availability of low-band spectrum (with fair geographic coverage obligations attached) and an effective reformation in the way we implement network sharing agreements will make wireless a viable option for the National Broadband Plan. Without these, fibre is the way to go, unequivocally.

Wireless brings many strings with it, strings which ultimately decide the future of rural Ireland and its very existence. Fragmentation is a string, and so too is the enormous cost to provide ubiquitous, future-proof coverage in a country where 76% of the land is occupied by farms and forests and where 3% of the population lives in 28% of the land area. The question is, how many strings are we willing to endure? Mobile providers have already met a glass ceiling, with further expansion being deemed not commercially viable.

Some would even argue that the demand for coverage is beginning to overtake the demand for capacity once again in many locations as the pervasiveness of high-speed fixed connections allows providers to shift traffic away from the RAN. In my eyes, the most astonishing revelation in ComReg's report is the conclusion that achieving ubiquitous mobile coverage in Ireland is not possible before 2070 without state intervention. If this is the case, we might not live to witness the end of the rural/urban digital divide in Ireland, and that creates a sincere sense of sadness within me. This is a massive alarm bell, a bell which will only scream louder as 5G becomes available in cities and towns, not rural villages and farms.

We need drastic and immediate action to solve the rural/urban digital divide before it is too late, and regardless of how aggressively we lobby our mobile providers to take action, the activation of a magic wand to solve all of our problems is not possible. Only the expansion of fibre distribution networks, increase in the availability of low-band spectrum (with fair geographic coverage obligations attached) and an effective reformation in the way we implement network sharing agreements will make wireless a viable option for the National Broadband Plan. Without these, fibre is the way to go, unequivocally.